Georgius Agricola – a renaissance scholar on mining

The humanist Georgius Agricola published his book De Re Metallica in 1556. The title means something like “on metallurgy”. The work covers the mining industry and everything related to it and ranks as one of the great scientific works of the Renaissance. It brought the surviving experiential knowledge of the miners together with the classical school of the humanists.

Mining already took place in prehistoric times. At the Limburg Rijckholt mining complex the remains of ancient flint mines are visible which date back to around 3000 BC. In the bronze and iron ages the extraction and processing of metal ores became of interest. Powerful states like the Roman Empire could only exist thanks to the availability of sufficient metals and other raw materials.

The history of Western civilization is inseparably connected with the mining industry. The prehistoric mines at Rijckholt already consist of an extensive underground tunnel complex. Nevertheless, initially quarrying predominantly existed at the surface or in shallow open grooves. With the increasing demand for metals more complicated mining systems were created. As tunnels got deeper, drainage and ventilation demands became more urgent. As a consequence, all kinds of technical innovations gradually entered the mining industry.

In Western Europe a blooming period for the mining industry began in the middle ages. The first important mines here were those at Goslar in the Harz mountains, taken into commission in the tenth century. Another famous mining town is Falun in Sweden where since the thirteenth century until the present day copper is being won. The rise of Western European mining industry depended, of course, closely on the increasing weight of Western Europe on the stage of world history.

In the history books more attention has traditionally been paid to generals, kings and artists than to things like mining and technology. Still, it is exactly these 2 areas that made the flourishing of Western European civilization to a large extent possible. On the other hand, the lack of interest is, however, understandable. Especially very little is known about medieval mining.

De Re Metallica: secrets of the mining trade

Mining was typically left to professionals, craftsmen and experts who were not eager to share their knowledge. Much experiential knowledge had been accumulated over the course of time in the following areas:

- the detection of ores

- building and maintaining tunnel complexes and all technical developments around it

- winning the metal from the ore

This knowledge was handed down orally within a small group of technicians and mining overseers. In the middle ages these people held the same leading role as the master builders of the great cathedrals, or perhaps also alchemists. It was a small, cosmopolitan elite within which existing knowledge was passed on and further developed but not shared with the outside world.

Their knowledge was in part probably still dating back to that in classical antiquity. Through all kinds of routes, among others through the Byzantine Empire, old Roman techniques had reached Western Europe. It is clear however that those mining techniques were going through a stormy development in Western Europe in the Middle Ages. As mentioned before we know very little of what precisely took place in that era. Our knowledge of medieval mining relies mainly on archaeological remains and on the legal organization revolving around the mining industry. Miners, and especially mining specialists, were highly regarded and enjoyed all kinds of privileges.

Still, only a few writers from that time write anything about mining itself. Partly that was because this knowledge was very difficult to access. Most writers also found it simply not worth the effort to write about it. Even though mining specialists were held in high regard, they were still considered (generally illiterate) craftsmen. Scholars and other writers were rather pre-occupied with higher things and looked down on something as banal as manual work.

Georgius Agricola: both a scholar and craftsman

Only in the Renaissance that perception began to change. In this time many scholars abandoned this haughty attitude and developed a lively interest for all kinds of issues previously deemed unimportant. With the improved transport and the invention of the printing press knowledge spread much easier and faster than before. In 1500 the publication of the first printed book dedicated to mining engineering, called the “Nutzlich Bergbuchleyn” (The Useful Little Mining Book”) by Ulrich Rulein von Calw. The most important work in this genre were, however, the twelve books De Re Metallica by Georgius Agricola, published in 1556.

Agricola (his real name was Georg Bauer) was born in 1494 in Glauchau in Saxony. He was the type of the learned humanist, the universal scholar of the Renaissance. He was friends with Erasmus, who vigorously promoted his work. His main job was that of doctor, but he studied all known science in that time. In his youth he taught Latin and Greek for a while; During this time he also published a Latin grammar. From 1524 to 1526, he resided in Italy, the “Mecca of science” at the time.

In 1526, he returned to Germany and in 1527 he was appointed city physician and pharmacist of the City St. Joachimsthal in the Ore mountains. St. Joachimsthal (the current Jachymov in Czechia) was only a few years earlier, in 1515, created after rich silver finds on site. In the time of Agricola it had already become one of the most important mining centers of Europe. A new, heavy silver coin was struck from the ore found there. This coin was named after the place of origin: “Joachimsthaler”. Abbreviated as “Thaler” this word soon became the denomination of all silver coins of this type. The English word for it was “Dollar”.

Around 1533 to Agricola returned to his native country. He settled in Chemnitz where he found the time to write and publish. As was befitting a scholar of his time he wrote about all kinds of subjects: history, ancient weights and measures, medical topics, theology, and so on. In addition, he was actively involved in the politics of his time. He was Mayor of Chemnitz and Councillor of the Dukes of Saxony. As such he took part in several national days and peace talks which were held in connection with the wars of religion in Germany.

His greatest interest, however, was focused on all kinds of subjects associated with the mining industry. He published writings on minerals and what we now would call geology. He also dedicated a writing to subterranean flows and — which may sound slightly curious — he wrote a book about underground animals. His principal work, however, are the twelve books De Re Metallica. It was Agricola’s last work. After he died, preparing to have sent away in 1555. The book appeared the following year, in 1556

De Re Metallica: Agricola’s life work

Agricola wrote his book in the scholarly language of that time, Latin. De Re Metallica literally means something like “about metallurgy”, but that title does not properly represent the content. The work gives an overview of everything that has to do with the mining industry. Agricola covers not only metals, although he gives them the most attention, but he also discusses the extraction and preparation of substances such as salt, saltpeter, sulfur and glass.

Although it is the last book that Agricola published, he must have begun with it when living in St. Joachimsthal. All in all he spent more than twenty-five years working on it. Although he also thoroughly studied the mining industry in his own country Saxony (Freiberg in Saxony was an important mining centre) the basis of his work are his experiences as the town physician of St. Joachimsthal. In this city he had deepened himself thoroughly in the mining industry. This interest was partly professional: he had to deal with many miner’s diseases in St. Joachimsthal. But for the most part it was pure scientific curiosity. He constantly visited the mines and workshops and dedicated whole study trips to satisfy his curiosity.

Of utmost importance were the dealings he had with some leading mining experts. Agricola apparently gained their trust, partly of course because they knew him as a doctor. Still Agricola did not come to know all the secrets of the trade. But thanks to these people he had access to a large amount of experiential knowledge that otherwise would have remained hidden. One of his miner friends, a certain Lorenz Berman, was the main character in a dialogue that he published when still in St. Joachimsthal. This dialogue, in which mainly mining knowledge is treated, can be considered a preliminary study for his later De Re Metallica.

“De Re Metallica” by Agricola, printed in 1556, which is featured in the new exhibition “Milestones of Science” at the Buffalo and Erie County Public Library, Wednesday, Nov. 18, 2015. (Derek Gee/Buffalo News)

Technical presentations in De Re Metallica

In his book, Agricola aims to give a comprehensive overview of everything which is mining related as he talks about the organization of mining and the various functions in the mines. He also offers practical advice, for example that it is unwise to start a company in a country whose ruler is a despot. Such an opinion is indicative of the time in which he lived.

He also speaks about the different types of reefs and the way to to detect them. Even though he extensively examined all traditional ways of the miners carefully, he was not prepared to take everything at face value. As a man of science he wanted those surviving practices critically reviewed. For example he was sceptical about the use of the “dowsing rod”, with which many had hoped to find new metal ores. Instead, as a scientist he tried to form a theory on the origin of those ore layers.

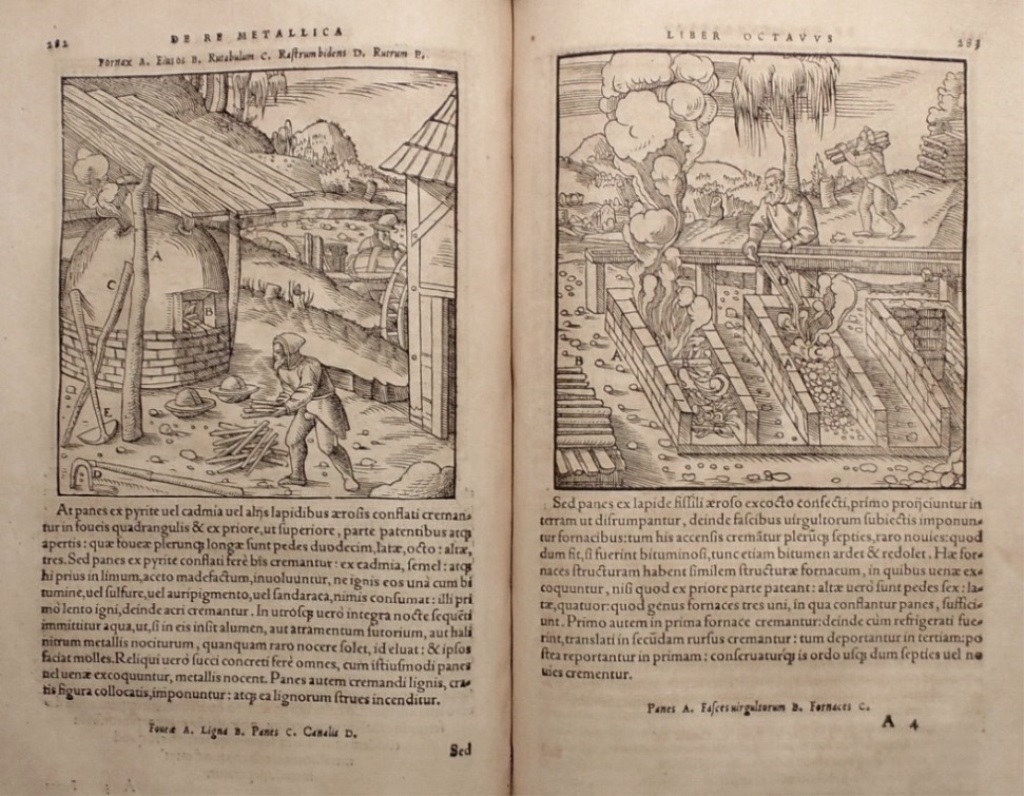

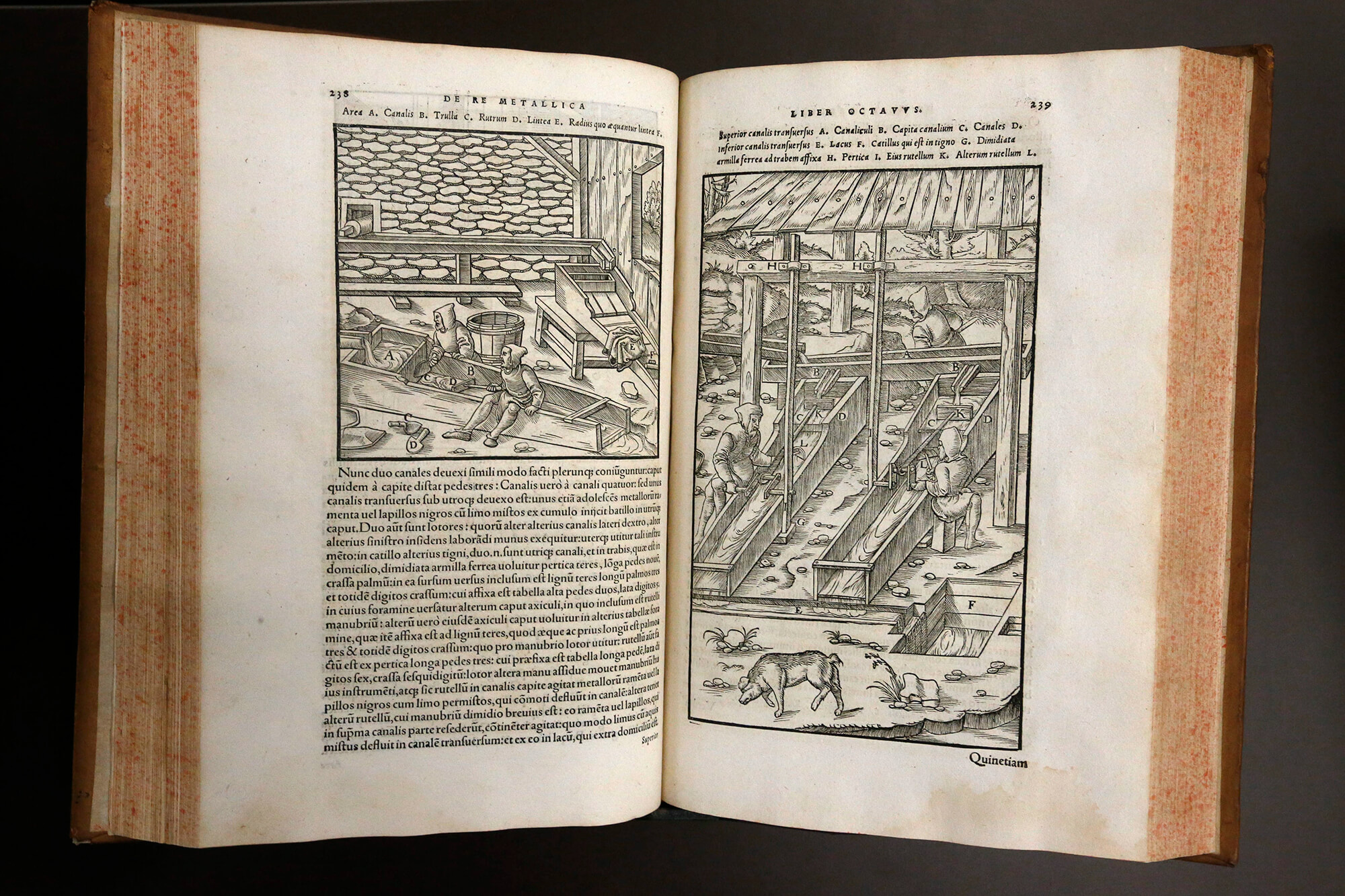

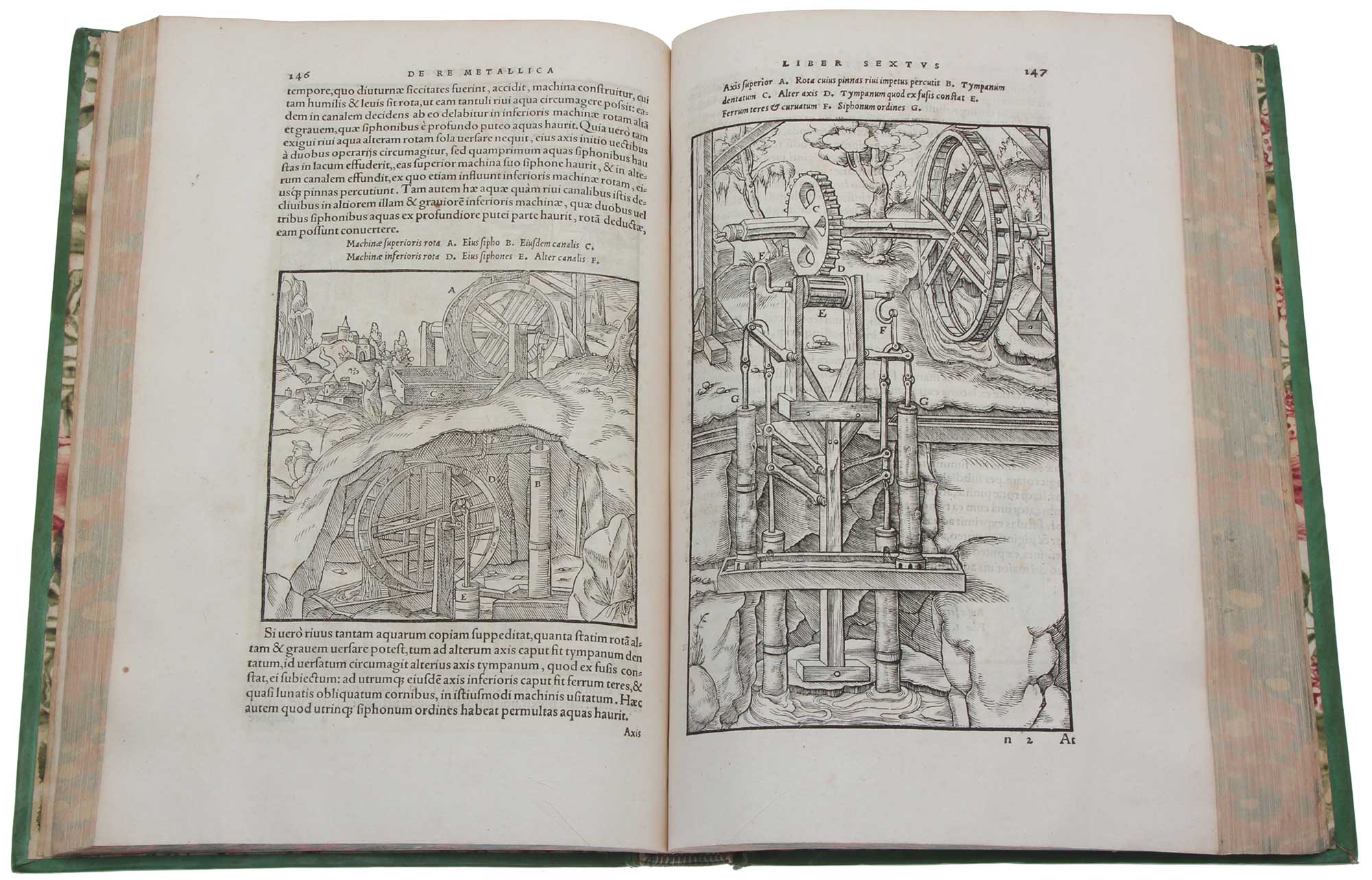

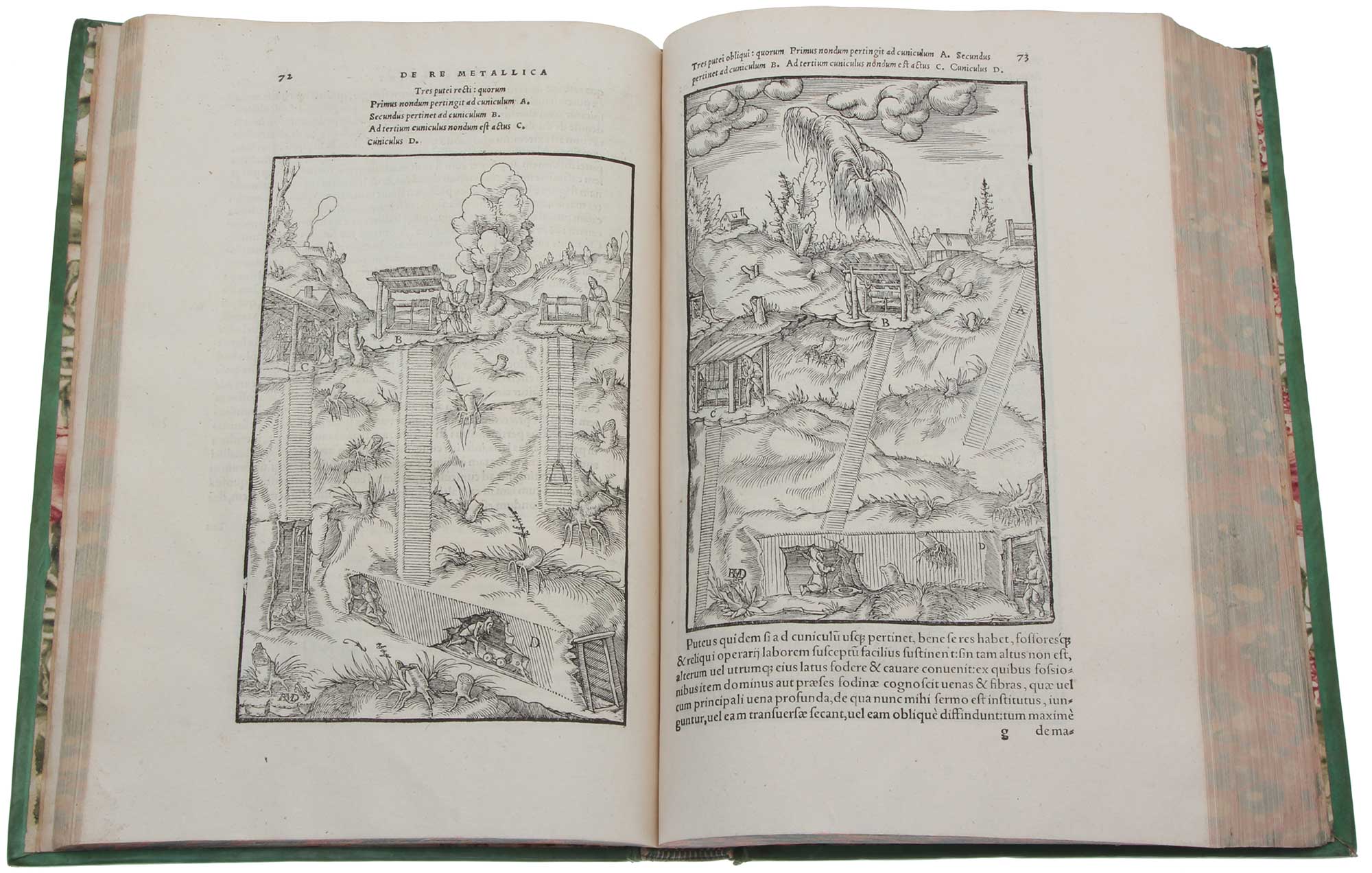

The most important aspect of his book, however, are the archetypal characters. He covers both the simple miner’s tools as well as the complicated installations with which the mines were being dehydrated and ventilated. Furthermore, the best approach to start a mine and much more.

Apart from discussing the actual mining practices, he also gives a comprehensive technical description of the many ways to clean and treat the ore and eventually separate the metals. Whomever possessed a mine usually also owned the means to further process the ore. As said Agricola also discusses other mining and quarrying products than metal.

What created the extraordinary value of the book are the many drawings and sketches Agricola used to illustrate it. He realized that technical descriptions in words alone are not enough to give a clear picture of the activity. Therefore, he provided clear images of all tools, installations and constructions that he discussed. These numerous images have contributed immensely to the fame of the book.

A new topic introduced in the mining industry

The very first portion of the book has a somewhat different character than the rest. This is a kind of introduction. Agricola is speaking here of the mining industry in general. As a true renaissance scholar he did so with a flood of scholarly knowledge and a large number of quotations from classical authors. He wanted to show that mining is a noble undertaking, incorrectly looked down upon. In short, that it is a worthy subject to be treated by a scholar such as himself. With this introduction Agricola shows how innovative his work really is. Former authors didn’t write about such topics. Agricola had, as befits a scholar, frantically looked up all kinds of ancient writers on the subject, but the harvest was very thin. Virtually his entire book is therefore based on his own observations and research.

For us, this is just priceless. But Agricola still believed he had to defend that he embarked on something new. The classical writers were considered “the alpha and omega” in science. Agricola was afraid that one would blame him leaving the path of the classical authors. Hence his comprehensive defending of the subject. The result is a book of which there are few: a bulky, beautifully illustrated work packed with information that is not known from any other source. A kind of encyclopedia of the mining industry and the technique from the time of the Renaissance.

But in addition, it was a book that drew the attention of the scholars on matters outside their layers of interest. A book that showed there were things beyond the classical writers which were worth knowing about and which became an example of accurate, independent research. Thereby it also helped establish a new kind of science.

Craftsmen and scientists in the middle ages

There is much debate among historians as to whether the practical craftsmen may or may not have played a role in the “scientific revolution” of the Renaissance: the emergence of modern science. Those who believe so, point out that the pioneers of modern science were usually people with a practical approach (for example, Galilei or Simon Stevin). The class of traditional medieval scholars, like those working at the medieval universities, had virtually no contribution to this scientific revolution.

Opponents of this idea point out, however, that all pioneers of science were formed in the traditional form of learning of their time, even though they departed from it later. Actual artisans among them are rare. In general craftsmen focuses more on tradition and very crude “hit or miss approaches” and they were not very interested in the establishment of novel theories.

But even if we assume that science was a case of literate or even university trained people in particular, then there was an impetus for these people to realize the limitations of their old-fashioned training. Science would never have arisen if the scholars only continued with beautiful philosophical theories without making their hands dirty. Physics is based in part on instruments and experiments.

That is why the book of Agricola is also historically important. It is one of the first works in which practical matters are discussed in a scholarly way. The book certainly stimulated the interest in such practical examinations and techniques. Especially because of that approach its significance to science cannot be underestimated.

The technical mining tradition

What Agricola had not realized, is that science can actually be helpful in the development of new manual techniques. The fact that people with a theoretical training apparatus and methods would take a closer look at practice and on the basis of their theoretical knowledge would try to improve those techniques. Agricola just wanted to describe the practice of the craftsmen. Once in awhile he gave an opinion as a scholar on the methods used or the ideas behind them. But he has not made any inventions of his own. Overall he remained a book scholar.

It was not until the next generation which insisted that science could be used to improve the technique, or even society as a whole. For someone like Agricola that step was apparently still too big. That later scholars could make that step, however, was also due to the fact, that they all were put on a new track by Agricola.

By the way, those early attempts to unleash science on the technique still don’t matter much. The practical barriers were simply too great anyway. Only centuries after Agricola were science and technology so far progressed that they could be valuable for each other. The interweaving of science and technique is mainly the work of the nineteenth century.

In the time of Agricola technique still entirely a matter of craftsmen who produced a stunning amount of work without theoretical knowledge but with a lot of experience and not to mention lots of inventiveness. Our current times have unparalleled scientific and technical capabilities. Though that is only possible through a technological tradition of centuries. And of this tradition De Re Metallica is a worthy monument.

Summary of De Re Metallica

This article discusses the book De Re Metallica of the humanist Georgius Agricola. This book, published in 1556, is an overview of everything that is associated with the mining industry. It is a monument of the technical ingenuity of the past. In addition, it is because it is a new sort of topic for the scholars of that time, a milestone in the history of science.

Literature

There are two modern translations of the book of Agricola. The oldest is an English translation, under the title De re metallica, by H.C. Hoover and L.H. Hoover. This originally appeared in 1912, published by The mining magazine; in 1950 a reprint appeared at Dover in New York. The second is a German translation, delivered from the Deutsches Museum in Munich: Georg Agricola, Zwolf Bücher vom Berg-und Hüttenwesen (Berlin 1928). Translating the work of Agricola is, because of the many outdated technical concepts, not easy, but both translations are carried out with great care.