Starting a Mineral Specimen Collection: How Build. 23 Criteria Tutorial.

This tutorial on how to start and continue to build the best possible mineral specimen collection of collector quality is published with permission Jack Halpern through Smartified. Edited by Wendell Wilson, Editor in Chief of the Mineralogical Record. Article published in 2008, still as relevant today.

Introduction

Mineral collectors tend to be as different from each other as clouds in the sky. We do share some similar characteristics, but each of us is an individual. Though we all share the desire to possess a fine collection of minerals, we each have our own predilections, our own preferences, our own motivations. As a result, our mineral collections are each unique, reflecting the diverse tastes, personality traits and technical training each of us brings to the hobby. This is as it should be.

Every collection reflects the particular eye and mindset of its collector. In a sense it amounts to his or her mineral fingerprint, but despite these variations the tastes of experienced collectors nevertheless tend to have certain basic tenets in common. As one among you, I have been guided by certain ideals in gathering specimens for my collection, based on the characteristics which are integral to many specimens in top-level display collections.

I aim to share these with you. You may or may not subscribe to these ideals yourself. However, choosing among the vast array of specimens offered for sale or trade can be a daunting task! The criteria listed below often direct the experienced collector’s eye and hand in singling out a particularly worthy specimen from the many thousands (actually millions!) offered for sale, and may likewise be useful to you in making your own selections.

For a display of mineral specimens in one’s home, different criteria may dominate over those which might apply to minerals stored in drawers, in boxes, in vaults or located on the backroom shelves of a museum where scientific study may be a paramount objective.

For a home display, it seems to me that visual delight should be among the primary satisfactions to be experienced by both the collector and his guests, whether or not those guests are themselves “mineral people.” Their response to the phenomenal world of crystallized minerals is a rewarding dividend that comes from displaying your selectively assembled minerals.

Following are my personal criteria for selecting specimens for a display mineral collection. Many of them were discussed by Wendell Wilson (1990) in his essay on “Connoisseurship in minerals,” and by Keith Proctor in his videotapes on mineral specimens. In the Proctor Collection (1988) and The Buyers’ Guide to Building a Fine Mineral Collection (2002). The criteria are presented in no special order, and many of them overlap, but I hope the list will serve as the basis for a useful discussion.

Criteria

1: Appealing Overall Form of Mineral Specimens

A pleasing architectural shape is a major attribute of a fine display mineral specimen. What is desired is an attractive conformation (or “composition”) about the entire specimen as well as about the arrangement of the crystals it harbors. Keen-minded collector Steve Smale uses the term “Good Horizons” in referring to a specimen with a generally pleasing aesthetic form.

2: Good crystal form

The shape of the crystals should be clearly revealed. They should be complete and undamaged, and ideally, they should be morphologically perfect.

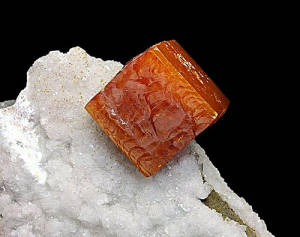

3: Clean, bright color of mineral specimens

Clear, vivid colors carry appeal. I avoid muddy colors. I vitalize my display with glowing greens, beckoning blues, radiant reds, opulent oranges, wintry whites.

Black minerals stand out much more clearly when they are interspersed among specimens exhibiting bright colors.

Red usually elicits major interest, hence the great value attributed to Sweet Home mine and other rhodochrosite, ruby, red beryl and cinnabar. The purity and “cleanness” of the color are important factors, and the presence of a color rare or unusual for the mineral adds to the desirability.

Generally, the deeper the hue, the better. Pink fluorite has traditionally been in high demand, but when it is deep pink it is more desirable; if pale, it is less so. Strong color contrast between crystal(s) and matrix also contributes visual excitement-as when, for instance, green dioptase studs a white calcite matrix, or blue-green aquamarine couples with deep pink apatite, or the green of emerald rests against the white of calcite, or red rhodochrosite cohabits a matrix with purple fluorite.

4: Mineral Luster

High luster delights the eye! I choose lustrous examples of a mineral rather than dull ones whenever that choice is possible. Brilliant luster is stunning in stibnite, cassiterite, quartz, vivianite and gold. A more satiny luster characterizes some benitoite, barite and rhodonite. The presence of lively luster rewards the viewer with visual stimulation, a quality often absent in dull-lustered crystals.

5: Desired Size of a Mineral Specimen

Generally, I prefer hand-size specimens, but many factors come into play here, such as cost and degree of acceptable damage. Also of significance is whether one prefers to collect specimens of various sizes or whether one specializes in one size category, e.g. thumbnails or miniatures.

The smaller the specimen, the greater the chance for perfection; thus more perfection is demanded by those who collect the smaller sizes. Also, the space available for display may influence the size-preference of a collector: a greater number of smaller specimens than larger ones may be accommodated on a shelf. Wendell Wilson once noted that most investment-grade specimens measure between one and six inches.

The upper size limit has increased somewhat in recent years, but this is an observation of interest to all who are concerned with the resale of their collections, by themselves or by their heirs.

6: Crystals and Matrix Free From Damage

Dings Deliver Demerits! Though sometimes I reluctantly accept some slight damage on a specimen, I have learned that the educated mineral buyer generally shuns specimens showing even minimal damage. The eventual dollar value of a specimen, when it is resold, will probably be markedly less if it carries any damage.

7: Crystals on a Mineral Specimen's Matrix

Just as appropriate framing adds aesthetic coherence to a fine painting, the presence of matrix adds visual appeal and value to a specimen. Additionally, the matrix often helps to pin down the geologic environment in which the mineral(s) crystallized, and it may help the experienced collector to confirm the locality of the specimen. It is basically for these reasons that crystals on matrix usually command higher prices than do comparable crystals which are no longer attached to the mother rock.

8: Crystal Transparency

Certain minerals sometimes possess the elegant quality of gemmy transparency. To me, transparency implies purity; it leads the eye away from any distracting features. As transparency is relatively rare, crystals that exhibit it are much more costly, in general, than translucent or opaque crystals.

And some gemmy crystals possess intrinsic value based on their potential value as faceted stones, independent of their value as collectible crystals.

Durability: this characteristic permits a specimen to resist breakage. Durable specimens may resist careless handling, earthquakes and other hazards; it is well to keep this in mind when making your selections for a display collection, even though vulnerable specimens of crocoite, mesolite or others may be appealing.

9: Being among the best of its kind

The prospective buyer would be well advised to learn the attributes of any mineral planned for acquisition, and to be aware of “the best it can do.” If one carefully reviews the offerings at mineral shows, looks exhaustively through museum and private collections, and studies the extraordinarily fine photographs appearing in journals such as the Mineralogical Record, one will sharpen one’s awareness of the elements of quality for each mineral species and occurrence.

Make friends with fellow collectors. Arrange to see their collections. Make mental or even written notes. But be forewarned: high-quality minerals usually command high prices.

10: Size Ratio Between Crystals and Matrix

A “comfortable” ratio is desired. It may be of interest to note that a large crystal on a small matrix seems somehow to be more acceptable than a tiny crystal on a large matrix. However, balance is best.

11: Crystal Relief

I prefer crystals which stand out boldly from the matrix over ones tending to merge with it or lie flat on it. With high-crystal-relief specimens, isolated crystals can be viewed individually, their edges not being concealed by edges of encroaching neighbors or by matrix material. The result is a greater opportunity to view the crystal in its entirety and to appreciate the awe-inspiring magic of crystal perfection and form.

12: Rarity of the Species

I collect a rare species for display only when the elusive specimen possesses what I perceive as eye-arresting geometry or great visual beauty. An example is the cumengite in my collection. It is small, but I find it geometrically amazing! My overriding objective is to bring delight to my mind and eye, and to reach out similarly to visiting viewers. Other collectors may be attracted to rarity for its own sake, even when this means sacrificing beauty. To each his own.

13: Focal Point in a Mineral Specimen

A “center of attention” on a specimen, when present, draws the eye and adds considerable interest, while the absence of a focal point sometimes relegates a specimen to the realm of the ordinary. A good center of attention usually takes the form of a particularly large, centrally located crystal.

14: Classic Mineral Specimen Localities

When superb minerals found long ago in a particular location have never been bettered in later finds, they are deemed “classics.” They are highly prized and eminently collectable, and the locality which produced them achieves fame among collectors.

The great “architectural” wire silvers from Kongsberg, Norway are a fine example. Acquiring classics is generally more costly, but it involves less risk to one’s investment. The mentally agile collector, though, may be able to distinguish from today’s mineral finds those specimens which bear the hallmarks of becoming tomorrow’s classics. Be alert! Seek them out!

15: Authenticity

Are the crystals natural, or were they manmade? Is the specimen a fake? Have crystals been glued onto a matrix or inserted into a matrix on which they did not grow? Is the locality appearing on the label a lie fabricated to mislead the prospective purchaser into thinking he is looking at a classic? I avoid such faked specimens.

I do business with purveyors of established repute, and count on them to apprise me, to the best of their knowledge, of any authenticity problems. Careful inspection of a specimen is recommended.

16: 360-degree Viewability

Some perfection-seeking collectors (such as Marshall Sussman) emphasize the appeal of 360-degree viewability. They especially appreciate specimens which may be viewed to advantage from all angles. If the back portion of a specimen is broken away, or if a vital part is missing from the front, this is a major flaw.

17: Recent finds-What to do?

Are more specimens of a desirable, recently discovered mineral occurrence likely to be recovered in the future? If so, should I wait to examine more examples before making my choice? Or, since the finest examples often appear in the initial offering, and are rapidly snapped up, would delaying be unwise? A reliable crystal ball-oxymoron-is required to resolve this disturbing dilemma.

18: Acceptable Cost

Is the specimen fairly priced? Experience, foresight and comparison shopping are the preferred ways to know; however, the delay that shopping around entails may result in your losing a desirable specimen to a faster-acting, more decisive buyer. And sometimes, even though a particularly desirable specimen may be overpriced at the time, you may later regret not having bought it anyway.

Everyone owns a few specimens for which they overpaid, and likewise a few for which they underpaid-it averages out. It is also true that if you moderately overpay for a truly fine specimen, the passage of time will soothe the sting. Anyway, the value of a superior specimen generally grows over time, and the initial overpayment eventually becomes unimportant.

Conversely, however, a low-grade specimen never achieves high value, either in my esteem or in the marketplace. I strongly suggest that you acquire the best specimens that you can manage to find. Buy fewer and buy better! Can I afford it? Does the specimen’s cost match my available means? Self-control comes into play here.

After experiencing acute financial discomfort from yielding to the allure of a large group of excellent specimens offered to me, but priced beyond my ready supply of funds, I now attempt self-discipline in the face of temptation. I have found that disciplined buying, though difficult, avoids later stress.

19: Special Characteristics in a Mineral Specimen

Distinctive factors such as fluorescence, twinning, phantoms, movable bubbles, or complete “floater” form may add to value and collectibility.

20: Past Owner Labels

The presence of historic, authentic labels made by previous possessors of a specimen may increase its perceived worthiness. Conversely the absence of any previous labels for an old specimen may detract from its desirability.

There is a certain glamour associated with a specimen’s past connection to a famed person or institution, and there is a stimulation arising from knowing that consequential people or organizations have appreciated the specimen sufficiently to have taken possession of it.

Any dealer deserving of respect will safeguard all early labels and pass them on to the new owners of specimens.From dedicated collector Bill Smith, I learned to use a separate glassine envelope to preserve past owners’ labels as well as my own, together with any other information of interest, for each specimen in my collection.

The envelope permits the collector to organize in one place all documentation associated with a specific specimen. Such envelopes, in a variety of sizes, may be obtained inexpensively from stamp dealers. I mark the envelope with the same unique identifying number which I have marked on the specimen. This procedure has proven invaluable to me, and will likely be equally beneficial for you and for your heirs when your beloved collection is being readied to move on to new owners.

21: Special Needs

Your own special requirements point to other criteria. For example, does the specimen under consideration fit well in size, style or specialization with others you currently own? Displaying one thumbnail in a collection of cabinet-sized specimens may create physical disharmony. Does the specimen satisfy your personal collecting goals? For example, you may have almost enough twinned calcites to fill a display case devoted to this specialty, but need one or two more. Does the specimen under consideration fulfill your need?

22: Specimen Enhancement

Man manipulates minerals. His hand is capable of transforming an unprepossessing rock into an excellent mineral specimen. Performing such alchemy requires knowledge, experience, talent, a keen eye and a steady hand. In some cases, highly specialized equipment and state-of-the-art techniques and chemicals must also be employed to prepare tine and worthy specimens for display.

Very few specimens shown in the offerings of mineral dealers appear as they did when first taken from the earth. After cleaning, sometimes in itself an extensive process, many specimens have been chemically bathed to remove unwanted coatings which obscured crystal surfaces. Then they were trimmed, a procedure in which the trimmer’s concept of an ideal shape for the specimen is realized.

The result of these operations is to allow more collectors to possess a greater number of specimens with appearances approaching perfection. Bob Jones has observed that were it not for certain steps taken to repair tourmalines recently mined from the Pederneira mine in Brazil, few of these extraordinary crystals would ever have reached collectors; the talents and patience of many humans have been employed to reassemble components into the major specimens we see today.

Improving the appearance of specimens raises ethical issues for many collectors; some, in fact, view any “repair” as intolerable. It would be wise for each collector to open his or her mind to the complexity of the problem, remembering that many acknowledged masterpieces of art in museums and private collections worldwide have had their bruises mended over time, and have thereby become again accessible for appreciation.

But it is precisely because collectors do differ in their tolerances of repair that any steps taken to restore wholeness to a damaged specimen should be declared clearly and openly, and the word “repaired” or “restored” should appear plainly on the label. If more space is needed to detail any major corrective steps taken, the dealer should prepare and staple to the label an accompanying card, the existence of which is noted on the label.

The ethics of the dealer and the level of his honesty are plainly laid on the line in the area of openly acknowledging repair.

Marc Wilson of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History has written a stimulating treatise entitled “The Four R’s of Mineral Specimen Enhancement,” recently published in Emeralds of the World: ExtraLapis English No. 2. Here are Marc’s four R’s as I interpret them, in order of decreasing acceptability:

22 a: Reinforcement

Glue or polymer has been applied to a delicate but unbroken specimen (usually to the matrix) to increase stability and strength.

22 b:Repair

Glue has been used to reattach broken pieces.

22 c:Restoration

An artificial substance has been applied to replace a gap in the specimen. This approach is still controversial.

22 d:Reconstruction

Artificial material has been added to replace a partial termination of one or more crystals, in an effort to duplicate the presumed original appearance. All such treatments are highly questionable, even if clearly and honestly spelled out on the labelIf any sort of treatment is suspected and is not acknowledged on the label, I recommend that the customer question the dealer on the point.The overwhelming majority of dealers operates above board and with full honesty, and could not succeed, long-term, in the business otherwise.I am personally grateful, however, for the technology which has been developed to reinforce, repair and restore crystallized minerals to a state permitting me to enjoy collecting them, and am indebted to such pioneers of mineral preparation as Bryan Lees of The Collector’s Edge, whose skilled staff has developed highly advanced specimen-preparation techniques.

Many others, such as Cal Graeber, are also adept in the science (and art) of specimen preparation. These people deserve our thanks for improving the world of the mineral collector.

23: The "Wow" Factor in a Mineral Specimen

very once in a while, there appears upon one’s horizon a specimen of overwhelming visual magnetism! It suffuses the collector with a sense of awe, and seems to challenge his belief that the earth could have conceived and gestated so magnificent a thing! If such a specimen comes your way and is within your reach, go for it!

These, then, are the criteria which come into play for me in selecting specimens for a display collection-the ways in which I say “yes!” to visual excitement. Thank you for granting me this privileged access to your own eye, and thus to your mind.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank Carolyn Manchester for lending her perceptive eye, and sharing her own finely honed sense of mineral aesthetics, in reviewing this essay. Thanks also to Thomas Moore and Wendell Wilson for editing the manuscript.

Source: Mineralogical Record

With permission: Jack Halpern