Dutch National Museum of Antiquities

The museum’s collection consists of no less than 80,000 objects. Quite a lot, considering the fact that the collection began with an inheritance of 150 Greek and Roman statues, left to the University of Leiden in 1744.

Willem I, one of the kings of the Netherlands in the nineteenth century, established a number of national museums. In 1818, he started the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden (National Museum of Antiquities) in Leiden. A humble house in the Houtstraat served as the first exposition room. At that time, people started to take an interest in the past. More and more citizens began to realise it was important to display cultural and art treasures and to preserve them for posterity. As a consequence, museums were established in the Netherlands, as well as in other European countries. These museums were places where collections were gathered and kept, and where the public could see them. In the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, all the collections of old, ‘lost’ cultures available in the Netherlands were brought together.

Reuvens

Caspar Reuvens was the first director of the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden. He was an enthusiastic man, the first in the Netherlands to organise professional excavations. Unfortunately, this pioneer of the early days of Dutch archaeology met with an untimely death in 1835. Notwithstanding his short life, he managed to expand the collection considerably. Special ‘art agents’ were sent abroad to purchase objects. Until 1830, the museum could dispose of ample government funds, but later these dried up for political reasons.

The collection grows

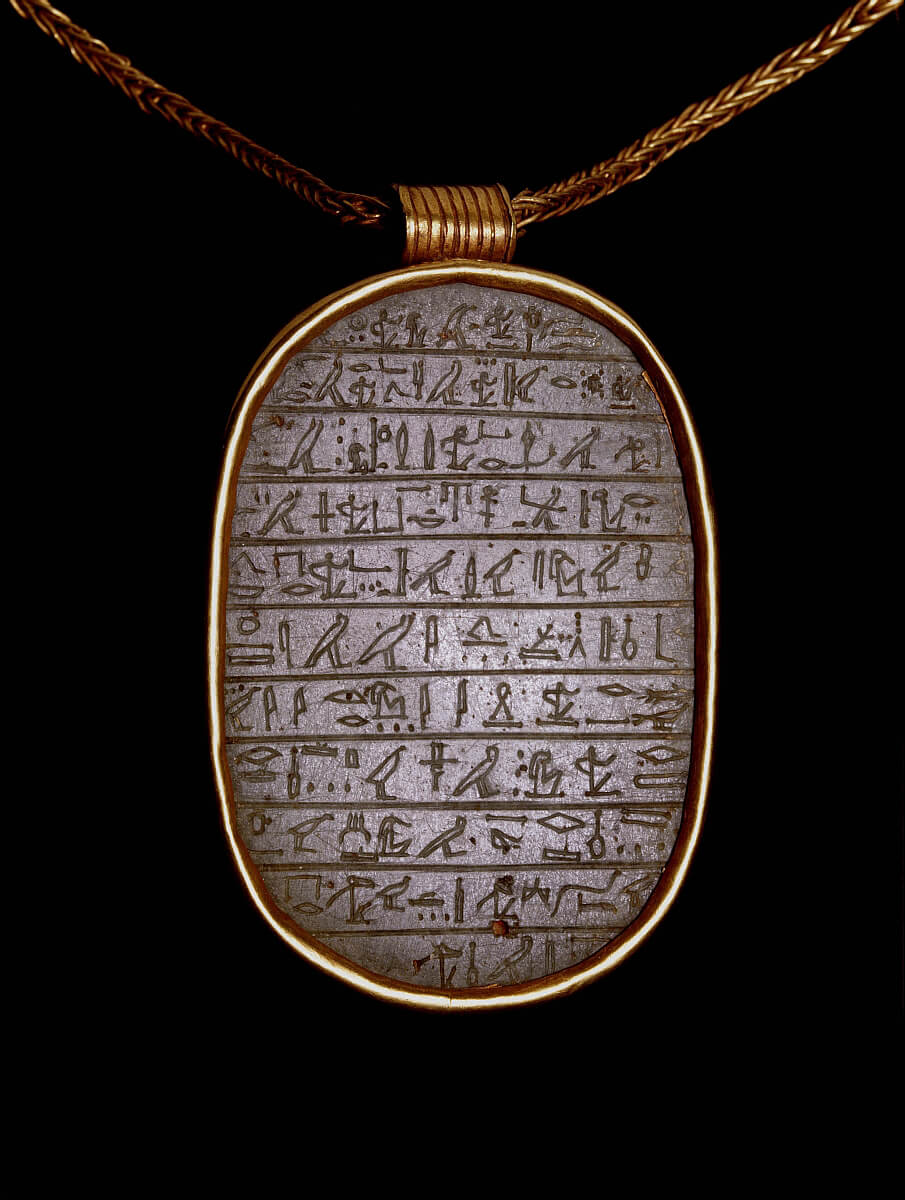

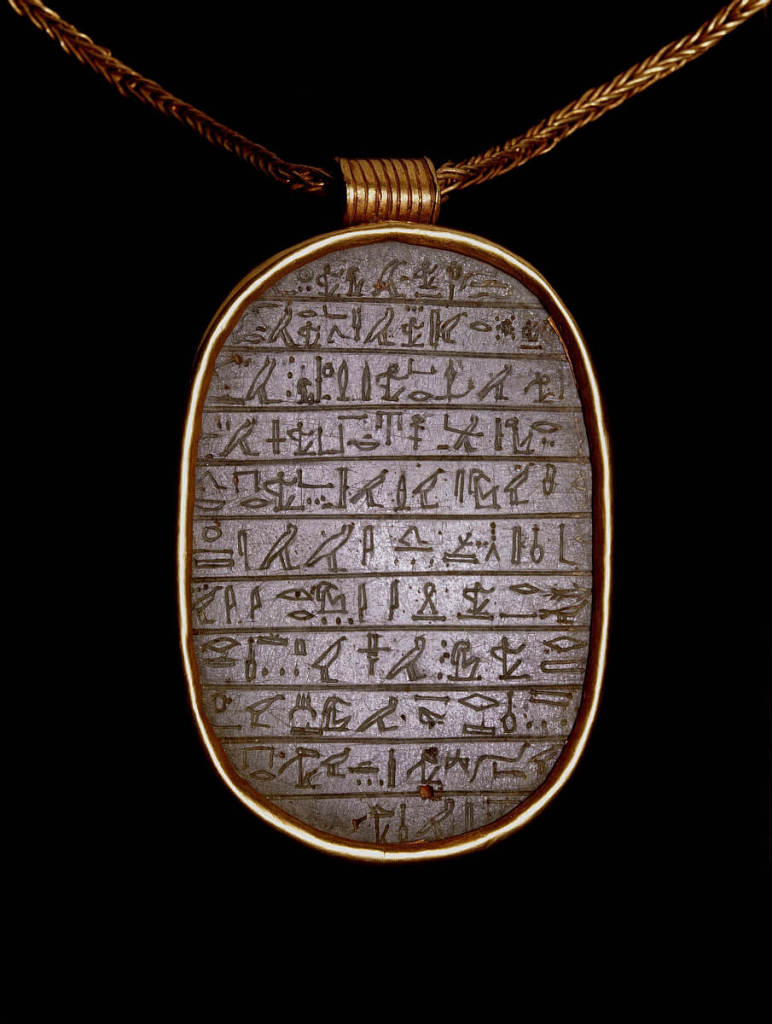

During the following years, many objects from Greek classical antiquity and ancient Egypt were added to the collection. These two were generally considered the most significant and interesting cultures of antiquity. After 1830, the collection mainly grew thanks to gifts and inheritances. And gradually, the cultures of the ancient Near East entered the picture. At the end of the nineteenth century, professional excavations were more commonly organised on Dutch soil, mainly by the museum itself. The museum’s collection was further expanded with the most important inland finds.

Adjustments

In the beginning of the twentieth century, the museum’s policy regarding the collection was adjusted. To prevent the museum from getting stuffed, it was decided to limit the excavation activities to those regions that have remained the collection areas to date: ancient Egypt, the world of classical antiquity, the ancient Near East and the early Netherlands. Objects from India and Dutch East India were discarded, for example.

New rules

Expansion of the collection now mainly happens through gifts (the Egyptian temple in the central hall was a gift of the Egyptian government), inheritance and direct purchases. The latter is a far more complicated matter in the twentieth century than it used to be in the nineteenth century, when a bag of money and permission of the local authorities often sufficed for a legal purchase of objects. In the twentieth century, these purchases are regulated by official treaties between countries.

Towards independence

In the twentieth century, more and more finds were made in Dutch soil. The large-scale building projects in the Netherlands made archaeological research ever more necessary, and modern archaeologists work in a more goal-oriented and professional manner than their predecessors. Finds of national interest are now added to the collection by ministerial appropriation. In 1971, the collaboration with the University of Leiden was ended. From that time onwards, the contacts between the museum and the national government have been more direct. The Dutch government subsidises the museum and is the owner of the collection. Since 1 July 1995, the museum has been an independent foundation in charge of the archaeological part of the national collection. Its task is to make this collection accessible to the public.