Torii Necklace Masterpiece, A Labor of Love

Love, the passionate beginning of many masterpieces be they poetry, art, or jewellery have inspired man to surpass the ordinary to achieve excellence.

Designer of the month, Cynthia Renée, took on the challenge of immortalizing one man’s love and devotion to his wife for their twenty fifth wedding anniversary. The end result, after three long years of hard work involving an extensive global search, meticulous examination of thousands of gems, delicate yet precise gem cutting, and expertise in color, creative design, and craftsmanship, the masterpiece we know now as the “Torii” necklace was created.

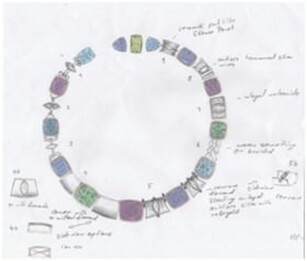

The Jewelry : The Torii Necklace handcrafted from platinum and 14-karat rose gold, featuring a suite of rare, pastel-hued cuprian tourmaline. The design process took 3 rounds in a 6-month period.

The Gems : 2011 American Gem Trade Association Cutting Edge Competition First Place-winning suite of 14 cuprian tourmalines from Mavuco, Mozambique weighing a total of 127.40 carats.

The Metals : An iridium-platinum alloy (Pt900/Ir) and rose gold were used for all parts but the prongs, which were ruthenium-platinum (Pt950/Ru) and all handmade. A total of 259 soldering joints were used throughout the entire necklace.

Love is as rare as the finest gems

The birth of the Torii Necklace originated three years ago with one man’s desire, to collect a suite of rare pastel shades of the copper-bearing (cuprian) tourmaline as a gift for his beloved wife. It was the at this time he called upon Cynthia Renee to source his vision.

First the gems had to be found and acquired. Yet, even with an expert’s eye, one had to straddle chasing the theoretical suite in the sky and being flexible with what is available in the marketplace.

Therefore, Cynthia began an extensive search followed by two intense weeks in Thailand meticulously examining approximately 800-1000 gems in order to complete the right balance of color, hue, texture and “feeling” for the necklace.

Selection at this point was focused on color. The next phase had to ensure the gems unity and balance together as a suite. Focus had to be on size and shape and therefore reworking the stones to achieve this was essential.

The Cut Above

The newly procured cuprian tourmalines, while delightfully colored, were all originally cut using primitive “native cutting” designed to maximize the weight of the stone, not their beauty, fire, or brilliance. The most common error in their cutting was a large face and shallow depth, resulting in a phenomenon known as windowing. This had the unfortunate effect of leaving an area of diminished color in the center of the stone causing some of the light rays to pass through the stone instead of being reflected back to the eye as brilliance.

One benefit of reworking poorly cut stones instead of starting with unformed, rough gems was that the interior aspects of the stones could be examined and their internal characteristics could be assessed. However, the ease stopped there. Somehow, the gems had to be unified into a suite of varying shapes: cushions, round, cabochons, squares and ovals.

Yet the more Cynthia pursued using a variety of shapes, the messier things became. If the 31-carat center pink stone was to be round, symmetrically, the other pink stones should be round as well but they didn’t want to be. Color-wise: besides the pink center, she didn’t want the suite to be loaded with all pink stones in the front.

Master gem cutter, Clay Zava, and his apprentice worked with optics and light alterations to determine how the light impacted the gem’s color and internal clarity since recutting could potentially expose inclusions heretofore not highly visible.

Additional challenges for the whole team included ensuring the outline for the necklace emphasized each stone’s clarity and brightness. Moreover, the cutting patterns had to be considered to ensure they minimized visual size differences between pairs of different colors.This endeavor required technical prowess and artistic vision from every participating member. It was not a project for the faint of heart.

Many hours were spent studying and brainstorming before the first cut had been made. A round shape was preformed for the pink center, without applying a facet pattern. This would allow the gem to eventually be faceted in a round or squarish-cushion pattern. Next, they entirely recut the two stones on either side of the pink center. The process of laying the suite would begin anew, with Cynthia and the cutters comparing the next two pairs to the round prototype and evaluating what needed to be changed and what seemed to be working.

After overnight reflection, it was decided to cut all the stones into Zava Mastercuts’ version of the cushion, “the pillow-cut”. This would unify the pieces thematically and eliminate the concern of varying cuts accenting the different internal clarities amongst the gems in the suite. The team was concerned that if the gems were all different colors and different cuts, the inclusions in some stones would really stand out compared to others that were cleaner internally. Having the same pillow-cut would unify them visually and homogenize the differences in internal textures.

Color Symphony

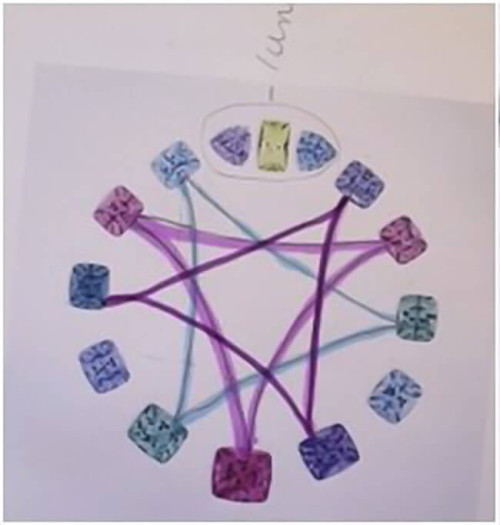

Aword must be said about the color order and placement, which was key to making the suite sing. Cynthia Renee thinks of colors as musical chords. When colors play well together, they can be a symphony. Sometimes they are discordant jazz. What she wanted to avoid was the color equivalent of elevator music.

At first look, the suite may be an ethereal bouquet, yet it is rooted in structure – similar to music that is intricately noted yet seems simple to the unschooled listener. The tourmaline colors had to be harmonious with those on each side of them and with their “sister pair” on the opposite side of the necklace.

Cynthia wanted the colors to “sound” and look harmonious, yet too much harmony can be bland. So, she punctuated the color like an arpeggiated chord by spreading the three different colors, lavender/pink/blue-green, symmetrically through the suite.

The result is a peaceful and harmonious tension that keeps the viewer’s attention. The tension is furthered by the symmetrical balancing of the center stone with the three clasp gems, which are opposite each other on the circle and of different shapes than the other stones.

The Torii Necklace

With gems so extraordinary, the goal of the necklace design was simplicity. The gems needed to take visual precedence. So it was decided platinum’s white gleam would allow the icy pastel gems to glow and a rose gold accent

(rose gold is alloyed with copper) would nod to the gems’ copper content.

Next was the design. Three rounds of design concepts were created in the Spring of 2013 before the final one was chosen.

Torii Gate design direction ultimately selected by her client due to his appreciation for Japanese art and it’s use of tranquil, serene, and meditative characteristics reflecting harmony.

Once the design concept was chosen, it was time for the design team to contemplate the engineering. Cynthia called on long-time friend and master jeweler, Mirjam Butz-Brown to bring the torii necklace to life. Working synergistically for two decades, Mirjam – with skilled hands and sharp intuition – knew how to translate Cynthia’s vision into the third dimension.

The Metals

The necklace would be primarily crafted using the technique of casting, with extensive hand assembly and some hand-fabrication. Casting is the technique where a model is made from wax, then cast in metal. Because of the primary use of casting and welding, palladium was not considered for use in the necklace as it is less reliable to cast cohesively and brittle to weld on. Also important, the necklace has many solder joints, and platinum is better for soldering on cast pieces. Two platinum alloys were used as well as rose gold in the 14-karat alloy.

There are two platinum alloys used: the iridium-platinum alloy, 900 parts platinum/100 parts iridium (Pt900/Ir), for building the baskets, torii elements and bars. Ruthenium-platinum, 950 parts platinum/50 parts ruthenium, or Pt950/Ru, was used to form the prongs. Because ruthenium-platinum has a higher melting point than iridium-platinum, soldering on the prongs crafted from ruthenium-platinum was safer with high temperatures. Iridium-platinum flows well for casting.The rose gold in the 14-karat alloy used contained 58% gold with the remaining amounts copper and slight silver. The presence of the rose gold spherical elements speaks to the unusual presence of copper in special gems.

The Engineering

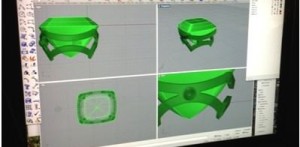

Artistic ideas can always be envisioned, but engineering is what allows them to come to life in ways that enable them to be worn and admired. This is an extremely important step that most jewelers dodge.It took approximately two weeks of working between the jeweler, Cynthia and the CAD casting technician to get the engineering finalized. This involved visualizing the finished piece from all angles that were then worked and reworked again.

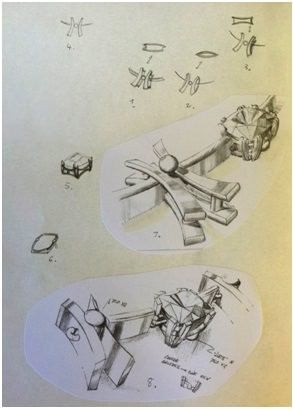

The Baskets It sounds poetic that the gems should sit in a basket, yet that is what that piece is called – the basket. After figuring out the basket shape and how the prongs and torii gates would attach to gems, the work began. After figuring out the basket shape and how the prongs and torii gates would attach to gems, the work began.

Aesthetically, it was important to see a minimum of attachment points face up on the necklace, so a plan was devised to attach the bars to the baskets unseen and face up. Further the prongs were handmade as cast prongs are more fragile. The iridium-platinum baskets were then cast separately with slight indentations where the eight wires forming the prongs were later attached.

The baskets and the rose gold elements were then cast using CAD modeling. To model the baskets, each gem was measured several times – not just length, width and depth, but the depth from girdle to culet. It was imperative that each basket fit each gem perfectly. The gems’ measurements were entered into the CAD Program.

Into each cast platinum basket, a “seat” was cut upon which the stone would sit. Seats help the gems sit as low as possible in the basket and must be cut carefully. If the stone is seated at even a slight tilt, it can crack during setting from an unequal application of pressure during setting by the prongs.

Another design challenge related to the seat cutting involved creating seats that allowed all the gems to sit at the same level in the necklace. In order to accommodate the visual differences created within the light and dark gems, each stone was slightly different. Therefore, each basket and each seat had to be tailored to the specific gem.

The Prongs

After the seats were created, eight grooves were cut into the indentations that were cast in the basket. It is here where the prongs would eventually attach. A slightly curved, hand-drawn prong wire was fit into those grooves. Each prong wire had to be filed correctly so the wire would not just fit in the groove but be the correct distance for the individual stone’s height above the girdle. It was important for the prong wires to be positioned to touch the stones at just the right points

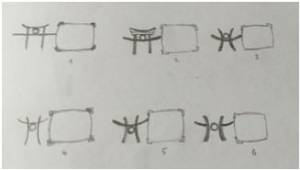

Making the Torii Gate Elements

In the Japanese artistic and philosophic view of wabi sabi, there is a grace and beauty in imperfection. Wabi sabi finds beauty in items that are imperfect and transient. There is an appreciation in natural objects’ irregularity, simplicity and integrity.

In order to remove the sterility of perfection and adhere to the Japanese philosophy, the choice was made to create the silver models for the torii gate by hand instead of using a CAD program. Hand-crafting allowed each side of the gate to be slightly different and unique, keeping in line with the aesthetics of an actual torii gate.

When plans for the torii elements were finalized, they included two different sizes to blend with the graduated sized of the tourmalines, with one size for a solid bar that would connect the toris to the baskets. Once in form, Cynthia and Mirjam agreed the smaller of the two sizes worked best. Mirjam then shaped the other toriis slightly smaller to taper around the neck.

The Clasp: Figuring out the clasp height, design, mechanism, workability and aesthetics took close to two weeks. The depressor mechanism had to be hidden in a way that was attractive yet functional. The box and tongue had to be shallow, with a safety bar underneath it. In addition, a heart was handmade in rose gold wire and soldered on the clasp’s underside with the couple’s initials inscribed and made to look as if they had been carved into a tree.

The assembly

The necklace was now ready to be mock assembled to perfect how it would lay on the neck.During mock assembly, the necklace was held together with temporary pins to see how it would hang and any necessary adjustments were then made.In all, the necklace was assembled five times, tweaking and adjusting so all the elements would lay just right.The tubings cast in each basket were drilled and adjusted.Adjustments also had to be made to the attachment bar lengths.To reach the desired 16-inch length, some of the bar lengths were shortened.This ended up working well, as the shorter bars blended well with the smaller toriis towards the back.

Once the stones were set, the torii elements were satin textured, then assembled, laser tacked onto the attachment bars, and soldered.The toriis were then drilled with a round burr to make a seat for the rose gold sphere designed to sit between the torii’s vertical, curved lines.The rose gold spheres were made using a square rose gold wire melted to form a bead on the end.Each rose gold sphere was then refinished, polished, cut from the wire, refinished again and inserted into the drilled seat where it was laser welded from the underside so the welding would not show from the top.

The final step in this spectacular process involved attaching the torii elements and bars to the baskets, using the technique we engineered to see a minimum number of attachment points face up on the necklace. The torii bars had a ring on their ends that slid into the tube we placed inside the basket. From underneath, a connecting pin of platinum wire was pushed through the ring in the tubing and then laser welded.

Final words:

Time is precious. Beyond love, time is often the most valuable gift there is to give. It’s easy to purchase a ready-made jewel for someone to enjoy and admire. But to love and respect someone so profoundly that a three-year commitment from start to finish was made to instill meaning and depth into each facet of this necklace speaks volumes.

From the detailed and extensive effort to collect the perfect gems to the aesthetic and technical virtuosity required to cut each stone to its own perfection, time was given. From envisioning and creating the design to crafting the necklace, time was given. From the 259 soldering joints on the torii necklace to the thoughtfulness inherent in the clasp’s meaning, time was given.

Finally it takes time to perfect a masterpiece be it love, marriage, or a work of art. This was truly a labour of love for all involved.