A visual – and colorful – sampler of Israeli Art Jewelry

Best read in landscape mode on your tablet or mobile

We are proud to present a selection from the book “Jewellery in Israel: Multicultural Diversity 1948 to the Present” by Iris Fishof. Iris focused on showing a selection of the most typical and colorful samples of her art jewelry collection.

Grains of barley and lentils (fig. 2.12) – was meant to bring her a good life, abundance and fertility. The shape of the bracelets worn by women after birth recalls house-like tombstones, a reminder of life and death (fig. 2.13). Different kinds of amulets were meant to protect newly born infants against evil forces, especially against the female demon, Lilith. A silver amulet made in Persia (present-day Iran), for example, shows the figure of Lilith bound in chains, with an inscription in Hebrew which explains the engraved image, and other Kabalistic incantations (fig. 2.14) (Shachar 1971). All those folk beliefs were soon to disappear as a result of the Zionist melting-pot doctrine. Throughout the early years of the State of Israel, the hegemonic ideology encouraged the absorption of immigrants by urging them to give up their culture of origin and forego their traditional dress, language and way of life, even to adopt new, Hebrew family names. Immigrants coming from Islamic lands and Europe alike were forced to give up their culture of origin. They were made to feel ashamed of their heritage and consequently hastened to part with decorative objects that had been part of their material culture. These found their way to the shops or flea markets (Chinski 2002), as well as to a few discerning collectors.

Page 33

Individual collectors of ethnic jewellery

Yossi Benyaminoff In Islamic countries, jewellery made in a variety of techniques and styles was given to a woman by her father or future husband. It was part of her dowry, solely her own possession, and she could sell it in times of need. Yossi Benyaminoff (1942–2011), an avid collector of folk jewellery from Islamic countries, was based in New York and Tel Aviv. His father, Nissan Benyaminoff, had owned a Jewellery shop in Jerusalem and was a jeweler in his Own right. The son vividly recalls women who would walk into his father’s shop, take off a pair of earrings and put them on the scales. Sometimes his father, noting a woman’s agony at parting with a beautiful piece of jewellery, would convince her not to sell it but rather keep it in the family. However, many jewellery pieces were in fact sold through dealers, who would arrive at the big city with a bag full of immigrants’ jewellery and offer them to jewellery merchants. Soon the souvenir shops of Jaffa, Tel Aviv and mainly Jerusalem had an abundance of ethnic jewellery.

As Jerusalem-born Benyaminoff describes it, “In the 1950s one could buy jewellery from immigrants in kerosene containers.” His own passion for folk jewellery from Islamic countries started at a very early age. As a young man he saw an exhibition of prints by Abel Pann at the Doron bookstore in Jerusalem and was thrilled by it. Pann’s depictions of biblical female figures (modeled on young Yemeni and Bedouin girls) wearing fabulous gold jewellery on their foreheads under their head covers (fig. 2.12) left a deep impression on him. “I was fascinated by those grandiose pieces of jewellery which no modern woman would dare to wear,” he says. His passion for Islamic and Jewish ethnic jewellery continued to develop after he moved to New York in 1966. He gradually built up a unique collection, parts

Page 34

of which are exhibited at the islamic Museum in Jerusalem and at the israel Museum, Jerusalem. A compulsive collector, he tirelessly hunted for beautiful and rare pieces all over the world (fig. 2.16).

William Gross was born in Minneapolis, USA, immigrated to Israel in 1969 and lives in Tel Aviv. He is known as the owner of a comprehensive private collection of Judaica. Within this varied collection of Jewish ceremonial objects, books and manuscripts, there is a collection of Jewish ethnic jewellery. Gross is primarily attracted to jewellery of talismanic nature,

such as amulets worn by Jews in islamic countries for protection against the evil eye and demons (figs. 2.17, 2.18) and for good fortune. He is fascinated by the khamsa (in Arabic, “five”), the palm-shaped amulet also known in Islamic countries as the hand of Fatimah, because it was popular among Jews and Muslims alike (figs. 2.19, 2.20).. In 2002, his collection of khamsas was exhibited at the Eretz-Israel Museum in Tel Aviv (Behroozi 2002).

Gross has acquired jewellery from collectors, from dealers, on expeditions abroad and through auction houses. like all fervent collectors, he is thrilled by

Page 35

Page 44

Page 45

Page 66

Page 67

Page 72

Page 73

Page 174

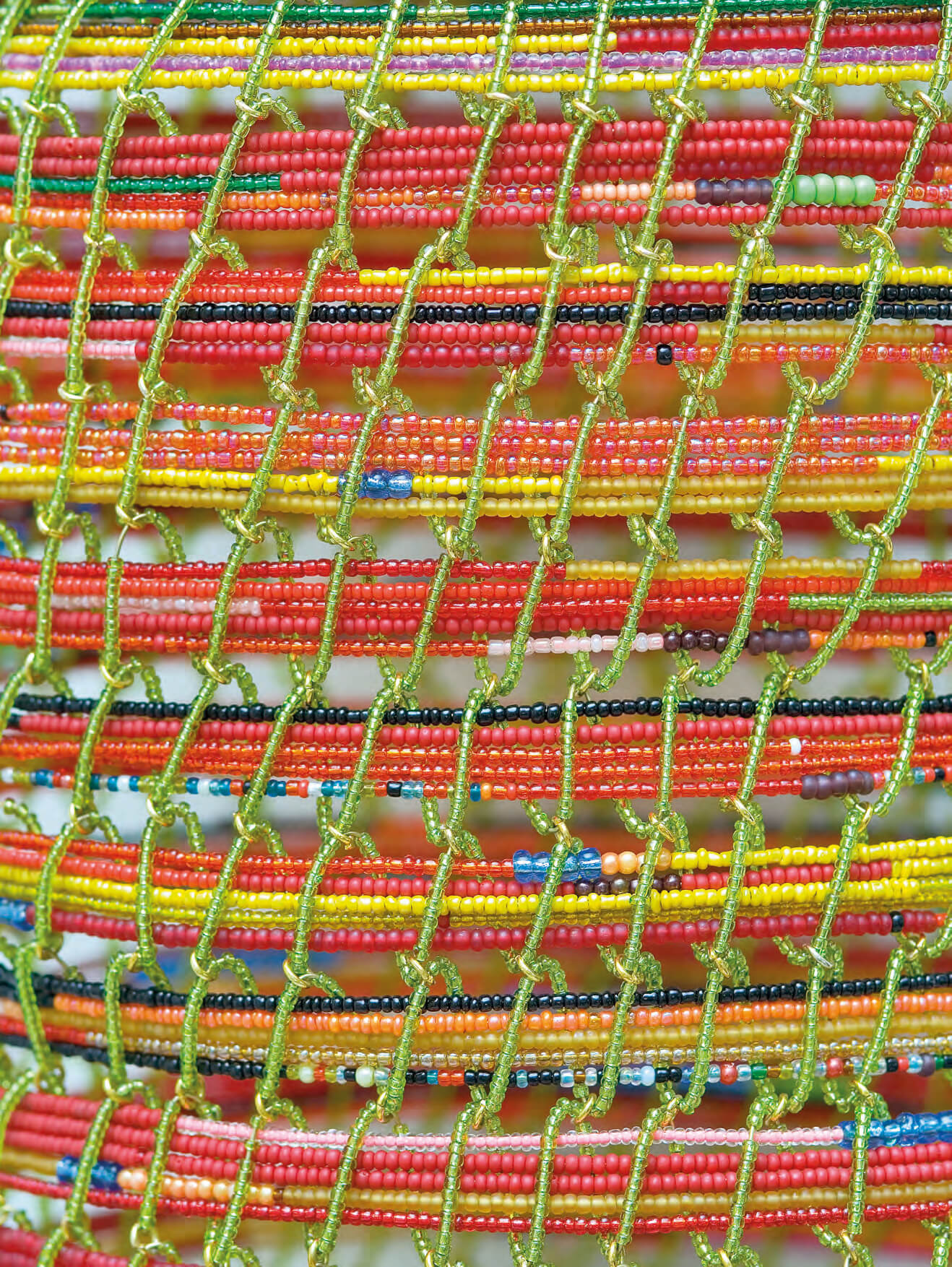

The cypress tree is also a prominent motif in the work of Ella Wolf, who was born in Romania in 1960 and immigrated to Israel in 1961. Wolf is a Bezalel graduate from 1987. She continued her studies at the Royal College of Art in London, where she received a master’s degree in 1989. She was only a year old when she came to Israel with her family. She grew up in Rehovot, a town famous for its citrus groves and where cypress trees are a common sight, dividing and delineating the groves. Wolf meticulously uses thread and glass beads (figs. 5.11 a, b) – echoing the folk art of Romania, her country of origin – to recount what she describes as “the roots and origins of my life. This life began in Romania but is deeply rooted in the Land of Israel” (Wolf 2012, p.163). Since 2001, she has been pursuing the theme of “the house and the tree” in works that straddle art, craft and fashion. As the daughter of a family of immigrants Wolf was impressed by the cypress tree, which is very strong, firmly holding on to the soil and resistant to winds. The house in her works has an emblematic

Page 175