The Human Body in Jewelry

Gijs Bakker, Friedrich Becker, Gerd Rothmann, Bruno Martinazzi

These artists belong to two successive generations, names that have been historicized in the international panorama of ornament as a form of research. In their works, the human body is the inspiration which is both faithfully and accurately reproduced and directly involved in the creation of the jewelry because of its specific physical characteristics, such as movement and the texture of the skin.

Simulacra

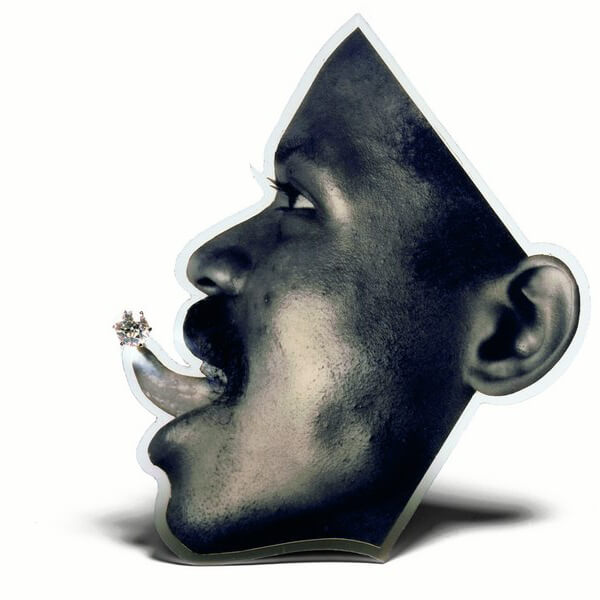

The abundant and varied work by the Dutch artist Gijs Bakker, one of the leading lights of new jewelry since the 1960s, has often examined and analyzed the special relationship between jewelry and the body.1 In this section there are some works that are distinguished by their use of the body in photographic form. Photography in jewelry, introduced by Bakker as early as 1976, allows the perfect reproduction of the subject and, with the process of PVC lamination, becomes the main material used in the piece. The photographic medium becomes an effective tool for an ironic, desecrating commentary on the world of jewelry and on society.

In The Tongue (Brooch, 1985), for example, we find the photo of a man sticking out his tongue which is adorned by a real diamond. Photographic images associated with precious stones – the cards have been shuffled, and there emerges the desire to destabilize, challenge the traditional values of jewelry, making literal fun of them and creating a real “gift for a deconstructionist literary critic”.2 From halfway through the 1980s the artist has dedicated a series of brooches (Sportfiguren) to the theme of the body sculptured by sport, a new aesthetic canon, represented by footballers and athletes in various disciples captured on film in movement and rendered ideals of beauty, to be worn almost as if they were contemporary trophies.

The beauty of the Michelangelesque anatomy of Adam in the Sistine Chapel, its position in the composition, the dignified impetus, the controlled tension of the figure and, above all, its world-wide fame have made the image the perfect subject for the Adam necklace (1988). Precisely inscribed on the ring of gilded copper, Adam turns and relates to the person who “will bring him to life” by wearing the necklace. Bodies that wear bodies: hints, quotations, references to art and society become interwoven in an intriguing network, drawing attention to the strength of jewelry as an effective, powerful means of communication and comment on the world in which we live.

Perpetuum mobile

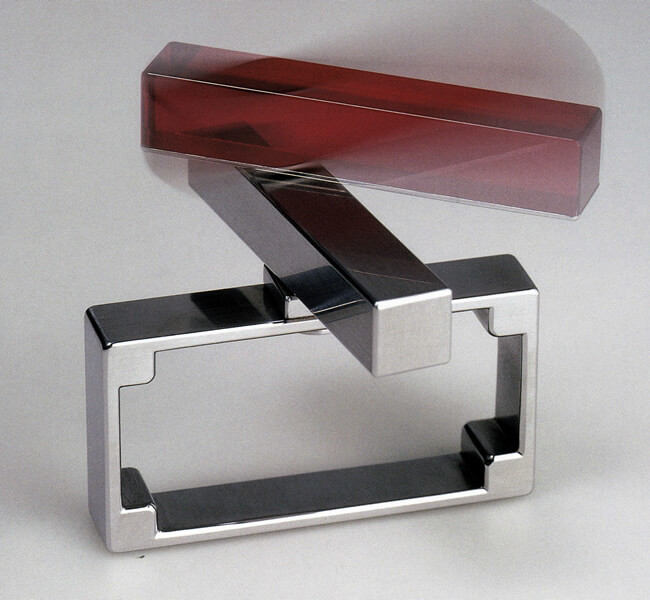

An important figure in the history of European research jewelry both as artist and teacher, Friedrich Becker, who has been working since the 1950s, has dedicated his art to the theme of movement in jewelry. From 1964 to 1997, the year of his death, the artist developed, studied, fine-tuned and produced an enormous number of variations of kinetic jewelry. The awareness of the fascination that the movements of the body can influence jewelry has been a constant in the history of jewelry, and ever since antiquity ornaments have been made that could pick up slight oscillations, vibrations of some elements. Later the aim above all was to amplify the sparkle of precious stones, diamonds in particular (en papille, en trémblant settings).

In Becker’s work the human body, its natural movements and its vital energy are at the centre of formal and technical research which is entirely programmed and participant in the contemporary developments in kinetic art. All his attention is concentrated on the creation of a pure geometrical shape, constructed through careful calibration of a mechanical structure comprising bars, pins and spoked wheels, artfully hidden from the eyes of the observer. Oval planes, parallelepipeds, cones, spheres – various elements make up Becker’s jewelry, but in reality their true essence, the reason they were made, only comes into play when they are worn, so that the person wearing them becomes an integral part of the objects.

The German artist’s poetic appears to be centred on the harmony between Mankind and technology, and the mechanical-geometrical aesthetics in his work, their absolute perfection, the technical sophistication and the attention paid to technical functionality are associated with a playful spirit, with the intention of awaking and stimulating the desire to play which is innate in the human character. The artist becomes a proficient magician who, thanks to his competence and skill, creates objects in which technology is not the end in itself, but the means through which he amazes and enchants not only the person who is an active participant in the game, but also all those who have the opportunity to observe the object in action and admire the dematerialization of the form through the rotation of its elements, the reflections of the light on the polished metal and of the synthetic stones on the silvery stainless steel.

His continuous search for new solutions, carried out as if experimenting with physical laws (the movements of his jewelry are linked to the principle of unstable equilibrium and integrated imbalance), is marked by an empirical approach based on experience which makes his works the subjects of an adventure in changeability, in which the human body becomes the motor force of perpetual motion. Friedrich Becker’s kinetic jewelry has a magic and attraction about it like modern examples of a Wunderkammer, but no longer confined to a private, inaccessible place: thanks to the fact of being worn in public, they become active provokers of a reaction, of a comment on the part of the observer.

The Impression

“Ce qui est de plus profond dans l’homme, c’est sa peau”. Paul Valéry, L’idée fixe

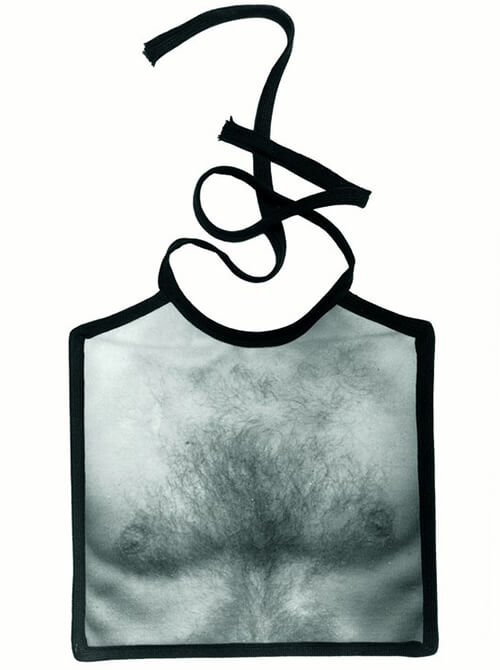

The peculiarity of the skin, a physical reality but also the final frontier of our being, the delimitation of our ego with respect to the world, a surface that records the most profound states of our being like a mirror, is the key element in Gerd Rothmann’s research. From the first works made in pewter at the beginning of the 1980s (Body Prints), details without a clear context modelled on a specific area of the body, the artist moved on to the impression of the palm of the hand. The special texture comprising the strong or weak lines on the epidermis, their extent and direction, contains and evokes the fascinating idea that they could be read and interpreted in relation to the fate of the person. From then onwards, the impression of the body, and of the hand in particular, has become the constant element around which his work revolves.

Through the artist’s mediation, a specific body makes an absolutely individual imprint on the material. The aspect that must be highlighted with Rothmann’s work is, indeed, the relationship with the commissioner of the piece, with whom he not only establishes a relationship (order – artist – artwork): in this case the commissioner is often “physically” involved in the production of the work. In one necklace, a mother can take with her the impressions of her whole family forever. The artist himself uses his hand as a physical signature in the Zeigefinger bracelet (1992). The body for which the object is destined will be wearing a work of art which is the result of personal research, but also a bodily mark, physical evidence of a relationship. In the work Von Ihm für Sie (1996), the impression of the male wrist becomes a bracelet that goes around the female wrist. The body is copied, perfectly reproduced, cast in gold and rises to become a wearable, visible token of love and the representation of a sentimental liaison between certain people (not a wedding ring but a much more incarnate symbol). Using an entirely contemporary language, the artist revives one of the ancient functions of ornaments, the sentimental, belonging to intimacy, the personal dimension of the most heartfelt affections. The fact that it is impressed in gold, an incorruptible material, means that the object can make up for an absence, render eternal something that is destined to vanish: “Inasmuch as it is impressed, it constitutes a stable identity that stands up to the fortunes of the flesh and of time, it is able to put up with absence, even definitive absence.”3

The parts for the whole

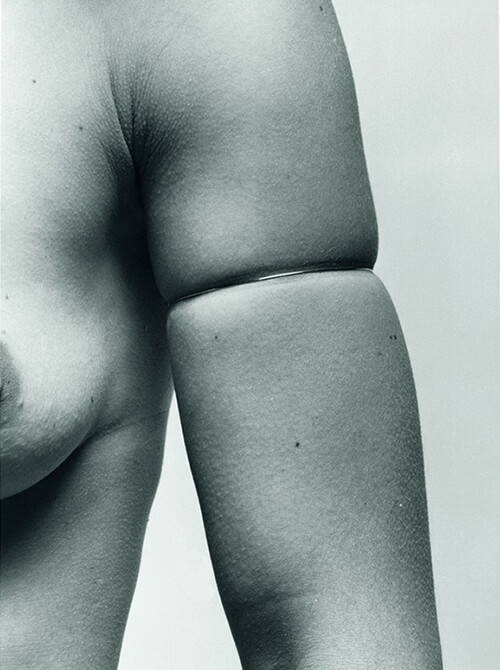

The parts of the human body are the main subjects for the jewelry by Bruno Martinazzi, whose research from the 1960s until today has been marked by a strong humanistic bend which has placed Man and worldly knowledge at the centre of his artistic approach. The Italian artist’s pieces are not fragments, not sections of a consumed entity, but rather clear representations of a part that refers to, suggests and recalls the totality, the whole. His jewelry, made of embossed and engraved gold sheets, are pervaded by a formal tension that gives it an animated, pulsating quality.

Parts that call to mind the sensuality of the female anatomy (Venus, 1980; Aphrodite, 2002), linking them to a mythical ideal of beauty. Ancient statuary is not therefore simply quoted with a yearning for a beauty which has now been lost, but rather its spirit lives again in the contemporary work, marked by a distinct and independent evocative strength that goes on to impress the sense of movement, the harmony of a taut body ready for action, as in the Atleta (2006).

The knowledge of the world comes about through the intellect being in tune with the senses: sight, hearing, smell, but also touch, and so the tools par excellence for us to experience reality are the hand and the mouth. The hand seizes, seeks and establishes a relationship with the other (Goldfinger, 1969), the hand with which do we not only get to know the world, but also act upon it (Homo faber, 1975); it is also a hand that has lost its definition, become bony, trying to cling onto something that it no longer understands, which has become foreign to it (Appiglio, 2005).

Delicate lips that meet and arouse the full force and magic, the pleasure of knowing and sensory exchanges with the other (Bacio, 1997); lips side by side, close to each other, to indicate soft, sensitive communication (Whisper, 2000); or the mouth, site of the logos, becomes the representation of the lack of understanding, and so that which moved together now becomes the origin of what divides, separates, and expresses the violent caesura of an irreparable split (Kaos, 1992).

The body, and in particular its parts, aspire to representations of the various aspects of humanity, of our relationships and of its sensitive, transcendent research, and so the act of decorating oneself with Martinazzi’s jewelry is a response to the need to communicate,

to render visible the deep-rooted need for study, to the questions that have always accompanied Mankind: “Thus Mankind, by wearing jewelry, symbolically express the need to transform themselves; not only by superficial transformation, their skin and profile, but to transform their very selves and their lives.”4

1 The artist’s continued interest in the human body is the very reason that selected works are presented in two different sections of the exhibition.

2 Quoted in H. Drutt English, P. Dormer, Jewelry of our time. Art, ornament and obsession, Rizzoli, New York, 1995, p.106

3 J. Fontanille, Figure del corpo. Per una semiologia dell’impronta, Meltemi, Rome, 2004, p.271

4 Bruno Martinazzi quoted in Martinazzi, Arnoldsche, Stuttgart, 1997, p.50