Kremlin Armoury

The Kremlin Armoury (Russian: Оружейная палата) is one of the oldest museums of Moscow, established in 1808 and located in the Moscow Kremlin.

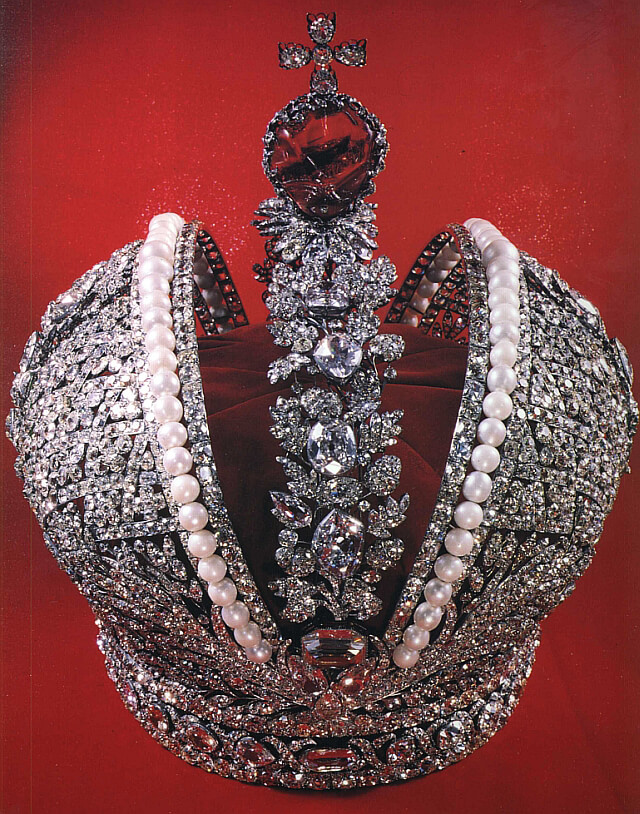

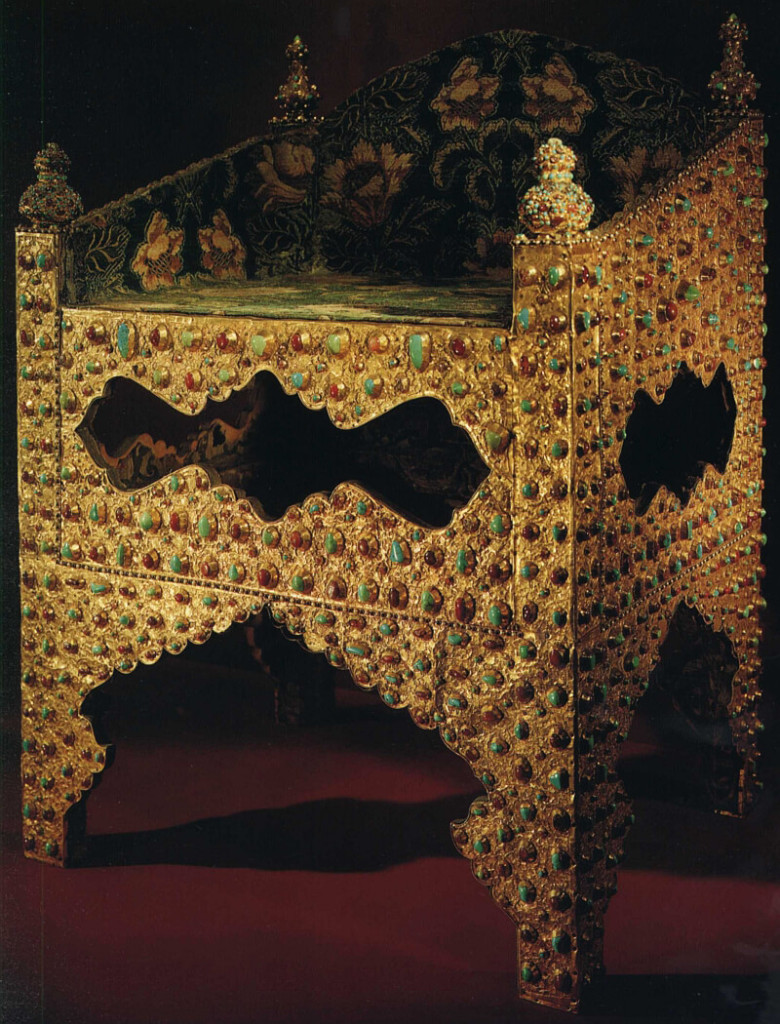

The Kremlin Armoury is currently home to the Russian Diamond Fund. It boasts unique collections of the Russian, Western European and Eastern applied arts spanning the period from the 5th to the 20th centuries. Some of the highlights include the Imperial Crown of Russia by jeweller Jérémie Pauzié, Monomakh’s Cap, the ivory throne of Ivan the Terrible, and other regal thrones and regalia; the Orloff Diamond; the helmet of Yaroslav II; the sabres of Kuzma Minin and Dmitri Pozharski; the 12th-century necklaces from Ryazan; golden and silver tableware; articles, decorated with enamel, niello and engravings; embroidery with gold and pearls; imperial carriages, weapons, armour, and the Memory of Azov, Bouquet of Lilies Clock, Trans-Siberian Railway, Clover Leaf, Moscow Kremlin, Alexander Palace, Standart Yacht, Alexander III Equestrian, Romanov Tercentenary, Steel Military Fabergé eggs. The ten Fabergé eggs in the Armoury collection (all Imperial eggs) are the most Imperial eggs, and the second-most overall Fabergé eggs, owned by a single owner.

Faberge: an Introduction

To most of us today the name Peter Carl Faberge conjures up memories of the extravagance and whimsicality enjoyed by a doomed society. It is impossible to think of him without recalling the surprise Easter Eggs and bejeweled mechanical trifles that he made to amuse the last of the Romanovs. We look at his work with mingled emotions. Inevitably, one yields to the fascination of gold and precious stones, and one is caught by the spell of his intricate craftsmanship. Yet for many of us there is an added interest, the tragic fate suffered by the Romanovs. Their costly indulgences symbolize, at least in part, one of the causes of their downfall.

The Jewel Age of Czardom

THE DIAMOND THRONE AND BLAZING ORB OF ALEXEI MIKHAILOVICH added awesome brilliance to his otherwise petty Court and superficially obscured the mediocre talents of the second Romanov Tzar who, during thirty-one years in the Kremlin, delegated to palace favorites all such headaches as wars with Poland, Sweden and Turkey — plus revolutions championed by the Ukrainian Cossacks — while he grieved over the execution of his contemporary, England’s Charles the First; genially presided over Court cultural innovations like the dramatic recitals of ‘ ‘The Prodigal Son” and ”Joseph Sold by His Brethren”; exchanged embassies with the Courts of Spain and France; married twice and sired fourteen children. The fame of one son — Peter the Great — would later rival that of any name in Russian history.

Until Moscow’s rise, no civilization had lavished more of its wealth upon the holy images of its faith than was the custom of Russia’s Church in the Middle Ages. Kremlin princes and lordly priests gave the finest of their earthly riches as a sign of devotion to cherished icons of Mother and Child. Then appeared the early Romanov Tzars, men who claimed an almost godly origin for themselves, who achieved ostentation rivalling the most sacred of all icons.

Rivers of jewels and the rarest of metals flowed unrestrained. Midas-masses of icon covers in the Kremlin today are relics of Alexei Romanov’s and Patriarch Nikon’s reign, an age when a nation’s treasury was hung upon its walls and kings, thus lost, all in God’s name.

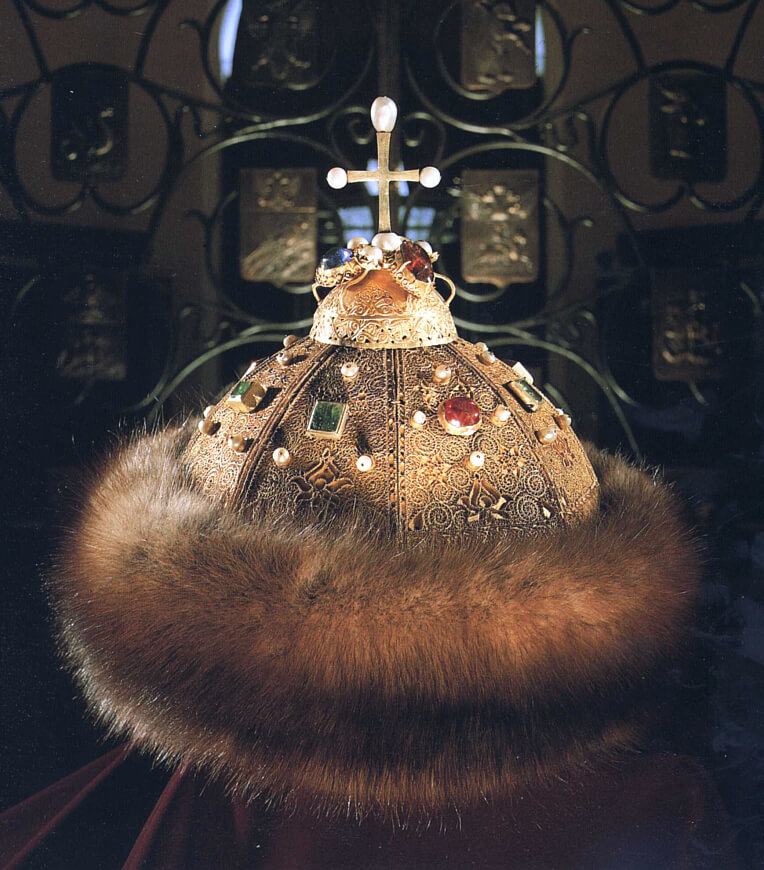

Monomakh's cap

A GOLDEN CAP was the treasure of treasures of every Grand Prince, all the Tzars, each Empress and Emperor ; it was the symbol of Divine authority invested in the Throne. It was the Cross and the Crown. Its haughty splendor had no rival — yet no one, not a single person had ever been able to say where it came from. It was just a Fact, like the sun and the night, like winter’s snow… like Eternity. It was the Cap of Monomakh under which every Russian sovereign had been enthroned.

Legend said — and it was one of the oldest legends of them all — that the Cap had belonged originally to Caesar himself, then later had been sent as a gift from a Byzantine Emperor to Vladimir Monomakh, Grand Prince of Kiev in the Xllth century. After Vladimir’s soldier-son Yuri Dolgoruki founded Moscow the Cap was brought from Kiev to the Kremlin. Everything related to the earliest history of the Cap was a legend, a legend based upon a political necessity: it was imperative during later generations that the Kremlin rulers nourish superstitious Russian peasant minds with tales of their dynastic inheritance as sanctified by God’s supreme Throne on earth, the Emperor of Byzantium.

Then, with the great peasant mass swearing an emotional allegiance to the Cap — but rendered politically docile — it was possible to firmly entrench and constantly extend the Kremlin’s realm. Regardless of whether it was fiction or fact that Vladimir Monomakh was the first Russian owner of the Cap, he actually did bequeath another shining legacy to his people — one which was thrown aside and soon forgotten, but which merited all of the respect and affection later bestowed upon his name.

It was only a word-covered bit of parchment — his final reflection on life and his Will to his sons: “It is neither fasting, nor solitude, nor the monastic life, that will procure you the life eternal — it is well-doing. Do not forget the poor, but nourish them. Do not bury your riches in the bosom of the earth, for that is contrary to the precepts of Christianity. Be a father of the orphans, judge the cause of widows yourself.

Put to death no one, be he innocent or guilty, for nothing is more sacred than the soul of a Christian Love your wives but beware lest they get the power over you. When you have learnt anything useful, try to preserve it in your memory, and strive ceaselessly to get knowledge. Without ever leaving his palace, my father spoke five languages, a thing foreigners admire in us …”

I have made altogether twenty-three campaigns without counting those of minor importance. I have concluded nineteen treaties of peace with the Polovtsui, taken at least a hundred of their princes prisoners, and afterwards restored them to liberty ; besides more than two hundred whom I threw into the rivers. No one has traveled more rapidly than I. If I left Chernigov very early in the morning, I arrived at Kiev before vespers.

Sometimes in the middle of the thickest forests I caught wild horses myself, and bound them together with my own hands. How many times have I been thrown from the saddle by buffaloes, struck by the horns of the deer, trampled underfoot by the elands ! A furious boar once tore my sword from my belt ; my saddle was rent by a bear, which threw my horse under me ! How many falls I had from my horse in my youth, when, heedless of danger, I broke my head, I wounded my armsand legs ! But the Lord watched over me!