Secrets of the Gem Trade 2nd edition

Secrets of the Gem Trade, second edition of Richard W. Wise’s Connoisseur’s Guide to Precious Gemstones builds substantially on the first edition, both are based upon the author’s personal observations over thirty-five years of buying gems around the world, together with a meticulous examination of more than three centuries of gemological literature. The second edition breaks new ground in his discussion of blue-white diamonds and includes perhaps the most comprehensive and sensitive overview of the aesthetics of jade to be found in the English language.

Gems are one of the oldest objects of man’s desire. What is the cause? What is it about gemstones that attracts us? In Part 1 (full book excerpt below) author Richard Wise probes deep into the human psyche.

PART I, Chapter 1

Becoming A Connoisseur: Essentials

Imagine a time before the existence of the world we know, long before the invention of artificial colors, aniline dyes or LED lighting. Picture a group of our remote ancestors, a party of Neolithic hunters, clothed in animal hides and armed with spears, picking their way single file, across a shallow mountain stream. One man stoops to drink. Out of the corner of his eye, he catches a tiny flash of color against the stream’s sandy bottom. He pauses, looks around warily, then scoops up the object and holds it up to the sun.

The oddly shaped pebble glows with the rich hues of blood and fire. The hunter’s curiosity is sparked, but he looks up, sees his comrades disappearing over the stream’s high bank. He stuffs the stone into a leather pouch tied to his waist, hefts his spear and scrambles to catch up.

That night a chill wind blows across the rugged escarpment. The hunters huddle in the shelter of a rocky cave roasting the day’s kill over a warming campfire. The spitting and crackling of the meat and the flow of its rich red juices jogs the hunter’s memory. He rummages in his pouch, extracts the curious pebble, squints and examines it in the it in the flickering firelight. The man is amazed. The pebble glows like a hot coal yet it remains cool to the touch. What is this magic? The hunter’s heart throbs with excitement. The man’s curiosity turns to awe and perhaps fear.

Other men crowd around, comment and reach for this new wonder, but seeing the greed reflected in their eyes, he snatches it back and stuffs it into his pouch. Later, alone, he examines the thing noting its straight edges and curious octagonal shape. Then, seeking to reach the gem’s internal fire, he places it on a large flat rock and strikes it with his hammer stone, but no matter how many times he strikes it, the pebble is unaffected. Next, he saws at it with his knapped flint skinning tool, the hardest object he knows, but the flint makes no mark the pebble’s surface., All he accomplishes is to chip and dull his blade.

What happened next is pure speculation. Perhaps, fearful of the tiny object’s magical properties, he brings it to the shaman, the wisest man in his village, who tells him that the stone is a manifestation of the sprits and appropriates it for himself. Perhaps he trades it to another hunter or, his woman sees and covets it. He wraps it with a thin strip of wet leather, dries the leather in the sun and ties it, the first pendant, triumphantly around her neck.

Curiosity…, Wonder…, Desire…! How many similar scenes play out daily in jewelry stores across the world? How often I have observed it working with clients.

Like a moth transfixed by the flame, our interest in these curious and beautiful natural creations seems instinctive. The first gem may have been the transparent pebble described above or a sunny yellow crystal caught in the firelight and pried from a cavern wall. Perhaps in the search for flint to knap into tools, a particularly beautiful piece of translucent agate caught a young girl’s fancy. Humanity’s desire to possess and adorn seems instinctive. The first known jewelry, shells perforated to make a necklace, were discovered in a Moroccan cave dating back one hundred thousand years.

The first gems were curiosities appreciated for their beauty and their unusual form. There were no preconceived notions of preciousness. Perhaps one of a handful of crystals had more pronounced color, was more transparent or possessed greater perfection of form.

The standards were instinctive, gut level. Even today, an untrained person shown a box containing several exceptional stones of the same variety will, in the vast majority of cases, instantly select the finest stone. The affinity is immediate. After years of contemplating the beauty of gems, I have determined that the basic principles of connoisseurship can be deduced from a thoughtful contemplation of a single fine gemstone.

For the budding connoisseur, the problem is that in a jewelry store one can see hundreds– at a gem show it is possible to see thousands – of stones. Under such circumstances, the eye is dazzled and the mind goes numb. Without a thorough understanding of principles, the budding but inexperienced aficionado is like the proverbial fatted lamb, ripe and primed for the slaughter.

Chapter 1

Precious Gems: The History of a Concept

“The clumsy modern category of ‘precious‘ stones has little relevance when applied to the ancient world.” –Jack Ogden1

Preciousness: Ancient Concept or Modern Prejudice?

In the West the distinction between precious and semi-precious appears to be a relatively recent one. The idea that one material was precious while another was merely semi-precious simply did not exist in ancient times.2 The word semi-precious itself entered the English lexicon only in the 19th century.

In ancient Egypt, for example, the color, not the type of material, appears to have been the primary criterion of value.

Egyptian taste in jewelry favored solid bars of vivid color, particularly blue and orange. Opaque and semi-translucent gems such as lapis lazuli, coral, turquoise, carnelian, and sard were highly valued. The masterpieces of ancient jewelry, such as those unearthed in the tomb of the boy king Tutankhamen, were beautifully worked in gold by skilled craftsmen. These treasures included gems such as turquoise and carnelian alternated with stones of faience 3 (a ceramic glass of melted feldspar) dyed to resemble a specific gemstone; in short, a fake! Was this due to a rarity of materials? It was obviously not a question of price. Were the Egyptian craftsmen misled by clever forgeries? Doubtful! The Egyptians simply placed a higher value on visual beauty than on the pedigree of the materials themselves.

Today with our rigid notions of what is precious and what is not, this seems odd. Would Cartier or Tiffany consider offering gold jewelry set with glass, plastic, or synthetic gems? Yet the glassmakers of ancient Egypt enjoyed royal patronage.4 The point is that the idea of preciousness is fluid. The popularity of gem materials has waxed and waned over the millennia. The truth of this becomes clear when we consider that much of the gem wealth found buried with the pharaohs of Egypt, at Babylon, and in the royal tombs of ancient Sumer is what many today would label as semi-precious.5

Descriptions in the Bible also clearly demonstrate that the ideas of the ancients concerning the hierarchy of precious materials differed markedly from our modern view. In Revelations (21: 9-21) an angel describes the heavenly city of Jerusalem as “having the glory of God; and his light was like a stone most precious, even like a jasper stone clear as crystal. . . . And the foundations of the wall of the city were garnished with all manner of precious stones. The first foundation was jasper; the second, sapphire; the third, chalcedony; the fourth, emerald; the fifth, sardonyx; the sixth, sardius; the seventh, crysolite (topaz); the eighth, beryl. . . .” Of the twelve gems named, only emerald and sapphire are commonly referred to as precious today, and although emerald was known to the ancient world, we know that sapphire was almost certainly the ancient name for lapis lazuli.6

The idea of a hierarchy of preciousness may have originated in the ancient East and worked its way slowly westward. In India, the oldest gemstone market, gems were broadly classified as Maharatna and Uparatna in the ancient texts. Of the nine gems of particular importance in those early times; diamond, pearl, ruby, sapphire and emerald were classified as precious. Topaz, jacinth (red zircon), coral and lapis lazuli were of lesser value.7

It is important to keep in mind that beauty was not the sole reason gems were valued in the ancient world. From earliest times gems have been esteemed for their magical qualities, as religious symbols, as talismans, as symbols of rank and status, and for their purported medicinal value.

In the Egypt of the pharaohs, carnelian symbolized blood. In ancient Sumer lapis lazuli represented the heavens. In classical Greece a man supposedly could drink his fill and remain sober if he drank his wine from a cup made of amethyst. To avoid eyestrain, the Roman emperor Nero reputedly viewed gladiatorial contests through an emerald lens.

In ancient China, badges made of gem materials were used to denote rank. Mandarins of the first rank wore red stones such as ruby and red or pink tourmaline; coral and garnet were reserved for bureaucrats of the second rank. Blue stones such as lapis lazuli and aquamarine symbolized the third rank. Mandarins of the fourth rank wore rock crystal. Other white stones indicated the fifth rank. Here again, color, not gemstone type, seems to have been the defining criterion.8

Gems were also valued as much for their talismanic or medicinal value as for their beauty. These arcane beliefs and associations persist today, but they no longer have any effect on value or the idea of preciousness, particularly as judged in the marketplace.

Seal stone engraving: value added

The carving of gems became an important art in ancient times with the introduction of seal stone engraving about 3500 BC by the Babylonians. Gemstones were engraved intaglio with mythical scenes that appeared in relief when the stone was impressed in clay. These engraved gems became the official signatures of kings, nobles, and high-ranking officials of the court. In ancient Mycenae, seal engraving reached a high degree of sophistication by the late Bronze Age. A group of seals recovered from Mycenaean shaft graves at Dendra (on the Greek mainland) shows a mastery of technique as well as a lyric sensibility equaled only by the Greek masters of the classical period and never since.9

The earliest seals were engraved in relatively soft stones such as serpentine and steatite; these stones could be carved using bronze tools. However, by the twelfth century BC, hard stones such as agate, amethyst and garnet became the materials of choice. Engraving these stones (over six on the Moh’s scale of hardness) required a more sophisticated technique: even iron, the hardest metal then known, was too soft to engrave carnelian agate.

Carnelian, the eighth stone of the breastplate of the Tabernacle’s high priest described in the Biblical book of Exodus, was the gem of choice for engravers from the Bronze Age until late Roman times. Fully fifty percent of Greek seals and more than ninety percent of Roman intaglios were carved of carnelian and the darker orange agate called sardius. The 13th century Arab gemologist Al Tifaschi, who did admit of a hierarchy of gems, classed carnelian amongst the “royal” or finest gems (‘al ahdjar al Mulukiyya’).10 Today the stone barely makes the semi-precious list, but carnelian was unquestionably one of the precious stones of antiquity.

By classical times seals were in use throughout the lands bordering the Inland Sea. Experts in this craft enjoyed high status. Some of the best quality gem material is found in Mycenaean gems unearthed at Aidonia. These are carved in the finest translucent layered carnelian. They are the exception: by Roman times, some of the finest masterworks of the engraver’s art were executed in opaque, relatively mundane pieces of dark orange carnelian and sard, demonstrating that the beauty of the material itself was of secondary importance. The real preciousness of the gem lay in the artistry and the quality of execution.11

The Middle Ages: shifting values

In medieval Europe, superstitions centered around the religious, talismanic, and medicinal properties of gemstones were accepted without question. Many of these beliefs had been passed down from ancient times in the writings of the Roman scholar Pliny and repeated in the works of the 7th century bishop Isidore of Seville. The medieval mind, obsessed as it was with questions of sin, death and the torments of Hell, proved fertile ground for the growth, dissemination and acceptance of such beliefs.

In those times, each gem was valued for its ability to protect its wearer from evils both physical and spiritual. “Coral, which for twenty centuries or more was classed among the precious stones,” cured madness and assured wisdom.12 Emerald was considered to protect the wearer against all manner of enchantments. Carnelian drove out evil and protected the wearer from envy. Lapis lazuli was a sure cure for quartan fever. Sapphire also offered protection from envy and was thought to attract divine favor. Chrysoprase protected the thief from hanging.

So universal was the belief in the magical and medicinal qualities of gem materials in the Middle Ages that it is impossible to discuss the value of gemstones in those times without reference to these arcane beliefs. Was the emerald valued for its beauty, or for its supposed value as a treatment for diseases of the eye?

Diamond: the invincible

Diamond’s fluctuating popularity on the gemstone hit parade further illustrates the point. Diamond was unquestionably the preeminent gemstone in India from as early as the 5th Century BC. India in those far-off times was the only source of diamond and had a flourishing gem-trading industry. The Romans, too, placed diamond at the very pinnacle of preciousness. By early medieval times in the West, however, diamond had fallen to number seventeen on the bestseller list. As late as the 16th century, the celebrated Italian goldsmith Benvenuto Cellini placed diamond third after ruby and emerald, with a price of only one eighth of what a ruby would bring. Writing in 1565, Garcia ab Horto, an early European traveler who described his trip to the gem fields of India, placed diamond at number three, but considered emerald, not ruby, to be the most precious gem of all.

One prominent scholar, Godeherd Lenzen, maintains that diamond’s early popularity in the western world was based not on its beauty, but on its durability and hardness. The characteristics that make diamond so desirable today — brilliance, dispersion, and transparency — are qualities that occur naturally only in well-formed, transparent diamond crystals. In Roman times, the technology did not exist to fashion or polish diamonds. Transparent well-formed crystals either were retained and sold in India (where they were highly valued) or bought up along the long overland trade route before they reached Rome. Thus, due to the rarity and desirability of fine crystals and the length of the overland trade route between India and Rome, the uncut rough stones that made their way to the ancient Mediterranean were of inferior quality; the attributes of beauty which make the diamond so avidly sought after today were necessarily unknown to the ancient Romans.13 Therefore, Lenzen argues, diamonds could not have been valued for beauty at all, but must have had some other attraction. The Greeks named diamond adamas, a word that means invincible.

This obviously relates to the gem’s legendary hardness, a virtue much admired in imperial times. Was it diamond’s “invincibility” that made it so attractive and valuable to the Romans?

To be fair, by the 17th century diamond achieved its current preeminent position in the gem world. The Portuguese subjugation of Goa in west-central India in the 16th century opened up more direct trade routes, increasing the flow of finer diamond rough to the West. The necessary technology for revealing the diamond’s unique beauty — polishing, cutting, and cleaving — was in place in Europe by the middle part of the century.14 Diamond’s preeminence is also a direct result of the development in the late 17th century of the brilliant cut. The 116 carat blue precursor of the Hope Diamond, brought to Europe by the French adventurer Jean Baptiste Tavernier, was recut in 1683, on the orders of Louis XIV, into the sixty-eight carat stellate brilliant that became known as The French Blue. This important technological advance in the lapidary arts unleashed, for the first time, diamond’s full potential — the astonishing brilliance and fire for which the gem is justly revered.15

- Jack Ogden. 1982.

- Jack Ogden, Jewellery of the Ancient World (New York: Rizzoli International, 1982), p. 90.

- Lois S. Dubin, The History of Beads: From 30,000 BC to the Present (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1987), p. 42.

- Dubin, History of Beads, p. 43.

- Ibid.

- Although the ancient Egyptians, from whom the Hebrews no doubt derived their notions of gemstones, knew emerald, some distinguished scholars believe that “emerald” (bareketh) was the name given to light green serpentine. George Frederick Kunz, The Curious Lore of Precious Stones (1913; reprint ed., New York: Dover Editions, 1971) pp. 292-301.

- Radha Krishnamurthy, Gemmology in Ancient India, Indian Journal of History of Science, (27)3 Should follow this order: Title of Journal Volume, no. Issue Number (Year): Page Number(s) 1992, p. 251. Other texts included as many as thirty-two gemstones.

- George Frederick Kunz, Curious Lore of Precious Stones, (Kessinger Publishing, 2010), p. 256..

- K. Demakopoulou, ed., The Aidonia Treasure (Athens: National Archaeological Museum, 1996), p. 51.

- Huda, S.M.A., Arab Roots of Gemology, Ahmad ibn Yusuf Al Tifaschi’s Best Thought on the Best of Stones, (London: Scarecrow Press, 1998), p.24. Al Tifaschi distinguished between al ahdjar al Karima gemstones that were rare and precious and those that were “royal” al Mulukiyya.

- Greek philosopher Theophrastus, in his treatise on gemstones, written toward the end of the fourth century bc, uses the word perittotera, which Calley and Richards translate as ”precious.” See E.R. Calley and J.C. Richards, Theophrastus on Stones (Columbus, Ohio: Ohio State University Press, 1956), p. 45. Other translators, notably Eichholz, translate perittotera as meaning “unusual.” Professor C.J. Fuqua of Williams College states that Theophrastus uses the term in the sense of more unusual, not more precious. Theophrastus does not use the superlative degree, “most unusual,” in this passage. There is no hierarchy involved with perittotera. (C.J. Fuqua, personal communication, 1999.)

- Kunz, Curious Lore, p. 69.

- Godeherd Lenzen, The History of Diamond Production and the Diamond Trade (London: Barrie & Jenkins, 1970), pp. 18-19. The Arthashastra of Kautilya, written sometime between the 5th and 6th centuries bc, characterizes a good diamond as one that is “regular in shape, capable of . . . reflecting light brilliantly in all directions.” Some scholars have held that this is a description of a cut diamond, and conclude that diamonds were cut in India as early as the fifth century BC. Lenzen maintains that the diamond described here is a perfectly formed natural crystal, and that such rare crystals were greatly desired in India and never found their way as far as Europe. According to Lenzen, the diamond crystals familiar to the Romans would have been gray, misshapen, barely translucent, and not at all beautiful. See also Kautilya, The Arthashastra, ed. and trans. L.N. Rangarajan (India: Penguin Books, 1992), p. 775. The second century bc writer Damigeron states “the best diamonds are found in India, second best in Arabia and the rest in Cyprus.” Lenzen, a scholar, not a trader, would perhaps not be aware that a stone may be purchased in Arabia but not necessarily remain there if a better price could be obtained in Rome. Damigeron, The Virtues of Stones, trans. Patricia Tahil (Seattle: Ars Obscura, 1989), p. 10.

- Lenzen, History of Diamond Production, p. 105. Although the crude process of faceting — by rubbing one diamond against another to wear each stone down — was known as early as the 14th Century, the technology for cleaving and sawing was not developed until the 17th Century.

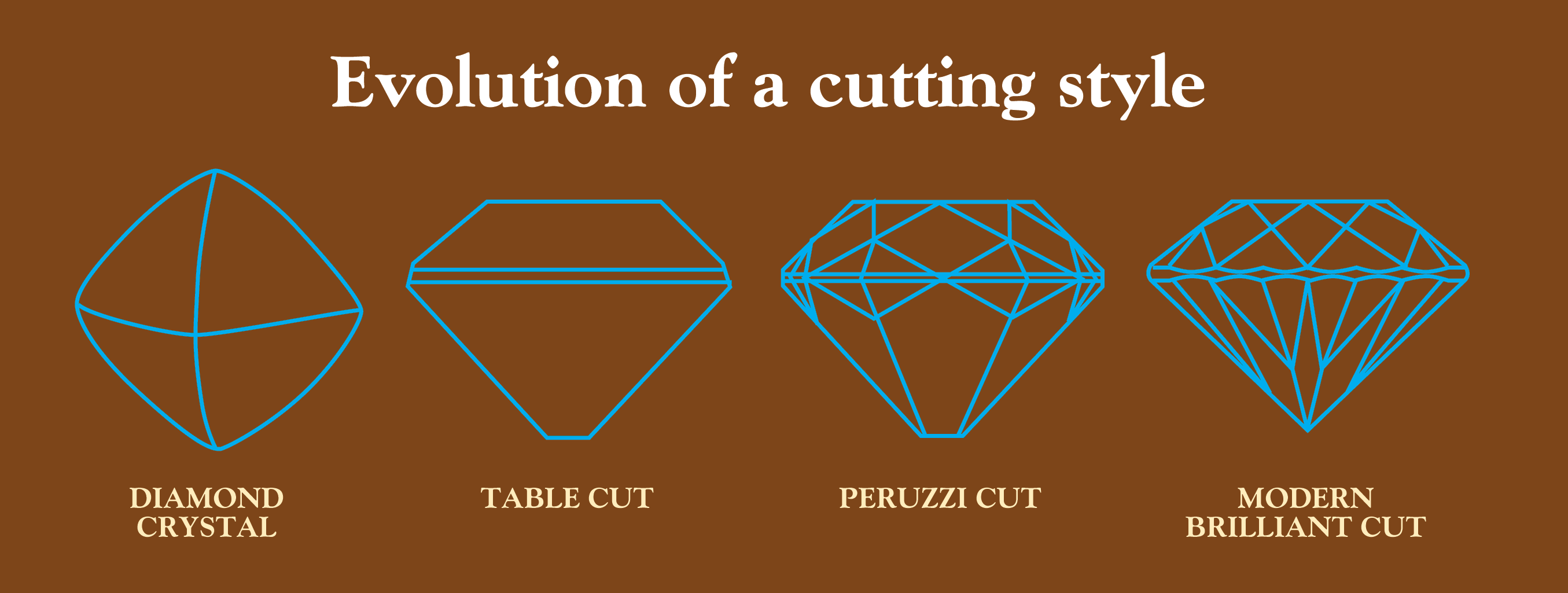

- Another famous 17th Century gem, the 35.56-carat Wittelsbach Blue. First mentioned in 1667 as part of the collection of Empress Margarita Teresa of Austria was also cut as a stellate brilliant probably either in Venice or Lisbon. vid. Dröschel, J. E., et al., The Wittelsbach Blue, Gems & Gemology, The Gemological Institute of America, Winter 2008, pps.348-352 Evolution of a cutting style: the basic outline of the natural bipyramidal diamond crystal, which evolved into the Perruzzi and thence to the modern brilliant cut.

About the Author, Richard W. Wise

Richard W. Wise is a Graduate Gemologist, retired gem dealer, author and lecturer. His articles on gemstone connoisseurship have appeared in Gems & Gemology, GemGuide, Colored Stone and Jeweler’s Quarterly. He is a former gemology columnist with National Jeweler and a former contributing editor with Gemkey Magazine and Gem Market News.

From the pearl farms of Tahiti to Burma’s famous Valley of the Serpents. From the opal diggings in Queensland to the ancient emerald mines of Colombia, Richard Wise has visited and done business in most of the major gem producing areas in the world.

Mr. Wise is the author of two books; Secrets Of The Gem Trade, The Connoisseur’s Guide To Precious Gemstones, a critically acclaimed best seller originally published in 2003 and The French Blue, a historical novel and fictionalized biography of the French gem dealer Jean Baptiste Tavernier.